Manuel Loff was 9 years old when Portuguese captains and soldiers, tired of being sent to Africa for a bloody war against the liberation movements of the colonies, overthrew the regime of António de Oliveira, who was already 41 years old , the most dictatorships Europe’s long-lived.

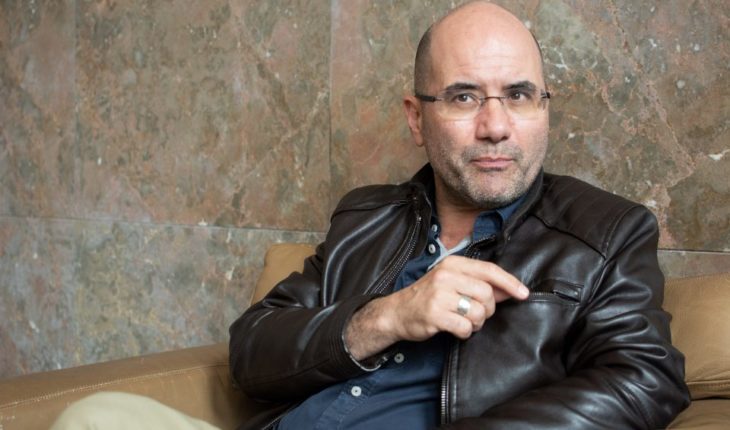

Today, at the age of 54, Loff is one of the most respected historians in Portugal when the matter is authoritarian regimes. Associate professor at the University of Porto and researcher at the New University of Lisbon, he accompanies with attention and concern the growth of the far right in the world. He has no hesitation in classifying Jair Bolsonaro’s government as a representative of neo-assis.

“His discourse on the social and political movements that oppose him, on women, ethnic minorities, family, nation, West forms a neo-assisisadapted to 21st-century Brazil,” he sums up.

Read: Hunger again overshadows Brazil

You have been studying authoritarian regimes for more than 30 years. What differences do you see between the far right of the last century and the one of now?

First of all, it must be said that there was already far right before fascism: since the beginning of the nineteenth century there was an anti-liberal and counter-revolutionary far-ahead, but it was very elitist.

The more modern fascist far right was born from the end of World War I, how the radical left was born as well. After 1945, there is a first cycle of the far right which, in much of European countries, although present, is outlawed. Thus, the far right from 1945 to 1968 or so is from a generation that lived through World War II, lived the Italian, German fascist regimes and fascist movements throughout Europe.

Then there is a second generation that is different from the previous one, who learned several of the lessons of the past. For example: he abandoned the openly racist discourse to move on to a culturalist discourse. Since the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945, racism has lost enormous space and, even if it is present, it cannot be assumed. Today, racists say their incompatibility with minorities is cultural in nature.

Read: Bolsonaro Project seeks to ban talk of politics and sexuality in Brazilian schools

Has the far right been growing in power and importance since the 1970s in the world?

The defeat of neofascism was a great defeat of the political culture of the right and meant more than at any political moment in history, a shift to the left of the social point of view, of political culture and of the triumph of the values of the left in democracy and a version of democracy that demanded a certain distribution of wealth and social welfare. So much so that most of the capitalist states of the “rich” West, who called themselves developed, adopted these social policies.

What we see today is an attack on all redistributive logic of social policies. The first version of a successful far-right in Europe was in Scandinavia: before attacking immigration, it focused on the welfare state, because of the weight of taxes.

His first target was the poorest, saying that he was creating a class of sloths who do not want to work, and then happen to say, more successfully, that immigrants came to suck from the of the welfare state.

Obviously, investing everything, pretending to ignore that any immigrant community, non-nationals, in any society, is on average much younger than the average of that society and works much more and earns much less, therefore contributes incomparably more with wealth production and social security.

What is the present moment of the far world right?

From the 1970s and 1980s, especially from the consolidation of the thesis of the clash of civilizations, the far right takes Israel as the forefront of the West in the fight against Islam and abandons anti-Semitism, which became a component clearly minority in his speech.

The target for immigration, especially if she is A Muslim. And that allows the South of the world to be combined with a characteristic that, for the far right, from an identity point of view, is central, which is religion. Because the far right never abandoned a description of the white and Christian West that colonized the rest of the world today, seen as a Judaic-Christian West heir to the two monotheistic religions of the Holy Book. This is particularly visible in the Americas, particularly in the United States and Brazil, through the new Pentecostal and evangelical churches that took a 180-degree turn in their view of the Jews.

That is, therefore, one of the evolutions of the far right. She tends to abandon the dimension of the denial discourse of the Holocaust, knows she has to, and concentrates on a new enemy, Islam. This culturelist racism creates a convergence platform of all the reactionary sensitivities that describe the immigrant as “the other” and attracts many people who did not share, or did not share, many of the other flags of the far right.

And then there is another point, which is very visible in the Latin American case, and in that sense bolsonism is the most complete and refined version of the far right, which is the discourse of the Marxist cultural dictatorship. From the thesis that there is a left-wing Marxist cultural dictatorship, the far right, on an international scale, moves forward with the explanation that it would have been imposed through the public school. Which means college and public school would be leftist trainers.

Deep down, with this thesis, they attack all the social sciences, everything that sociology, anthropology and history say. And in Brazil that took much further, politically, and more effectively, with the School without Party movement, whose thesis is that all social sciences are committed, militant and therefore none of them is objective. All of them would seek, for decades, to undermine the foundations of nature, community, social order: family, homeland, nation, etc.

There is even another thing that is very visible in Bolsonaro’s speech, and also in that of Trump, which already existed with Berlusconi, which is the role of women in society. I don’t even mean the LGBT universe anymore, but particularly women. It is the thesis that all feminism is radical, it is an invention of the cultural dictatorship of the left and what it intends to do is to legitimize an “offensive against God”, as the minister of foreign relations of Bolsonaro would say. And, according to them, what is the best way to assault God and the social order and the family? Transforming the role of women in families and creating new forms of family.

And the Brazilian far right took that much further, I do not think from the point of view of theoretical formulation, but much more successfully than in another country.

You defend the thesis that the world has been experiencing an “authoritarian transition” since September 11, 2011. And Brazil, at what point would it be on that path to the end of democracy?

Brazil is one of the most advanced cases, because the current government’s political agenda includes an open, explicit program of repression and intimidation of adversaries, threat of illegalization of the largest opposition party, repression on movements threat of arrest of opposition political leaders.

Authoritarian societies are not simply those in which the State is authoritarian, but also in which society is authoritarian. What is about to happen is an intimidation of the adversaries that will reduce the ability to maneuver social oppositions and social resistance—potentially so, now we need to see the results of reality.

You may be interested: Jair Bolsonaro assumes the presidency of Brazil: these are 5 challenges he will face in 2019

Is that typical of a neo-fascist state?

This is typical of a state in transition to authoritarianism that may or may not bring together all the classic characteristics of fascism. But that’s like democracy. Are the states in which we live purely democratic? I have a lot of doubts about that. When we talk about fascist regimes and democratic regimes, we talk about processes of permanent construction of democracy and fascism. Authoritarian transition begins when democracy is degraded. And it ends when there is no more democracy. It is now necessary to establish whether there is no longer a democracy in Brazil.

Do you consider that the government of Bolsonaro has enough characteristics to be called a fascist or neo-fascist?

Fascism does not prevail, as I said, overnight: Bolsonaro’s government program is so socially reactionary and, in its attempt to merge the interests of Brazil’s political and economic rights, it must assess the need to use institutional, paralegal violence that is beyond the reach of any democratic government. If you do not hesitate to use it, the practice will be very close to the fascist approach. His discourse on the social and political movements that oppose him, on women, ethnic minorities, the family, the nation, the West, forms a neo-hascism adapted to 21st-century Brazil.

Whoever argues that the government of Bolsonaro is not fascist says that it is impossible for there to be 50 million fascists in Brazil. But I think of the phrase you wrote in an article recently: “The fascist regime is not based only on fascists.”

Never, at any time in history was he born or consolidated only with fascists. Indifference is as central to sustaining a regime as the level of support. It’s totally ahistorical and asocial imagine political solutions, however totalitarian they may be, supported by 100% or 99% of people. They only survive if they have a very small minority and without support, or without sufficient support, that they are resisted and on which such “economic” repression can be exercised.

And you need to have a sufficient level of support, which can even be very small, since there are a large majority of indifferent or intimidated. And in all the authoritarian solutions there is an economy of violence, there is no violence on everyone. When exaggerated, when the exercise of violence is lost, the reaction may be too strong and may, for example, provoke a civil war and the defeat of the oppressive regime.

Going back to the question of attacking feminist movements, is that sexist, retaken-power speech one of the hallmarks of this new fascism?

There is an obvious fallacy and neopatriarchalism in all of this. The far right rarely openly assumes the defense of social and political inequality between men and women: it merely defends what the traditional family was. Many of the speeches the far right has had since 1945 are speeches that transform the perpetrator into a victim.

For example, ex-combatants of offensive wars perpetrated by several Western countries in victims of the war itself; in Brazil, the military who tortured themselves into victims of left-wing guerrillas, just as in the United States they transformed Vietnam War fighters into victims of the Vietnamese.

The same thing is done with men today, as is done with the employer who is the victim of an employee who does not work and is powerfully defended by a union, the state-submitted patron who steals his taxes. It reinvents the organization of society and invests everything: man, in the end, is the victim of feminist women, or the employer is the victim of the employee… And in this way he recovers as victims of contemporaryity, of the democratization of social relations, those who were/are the dominant groups.

If in Europe the far right uses the “threat” of immigration to encourage fearspeech and win votes, in Brazil the devil is communism, even if they apparently don’t know very well what it is and who is communist.

But they know why they use communism. It is very revealing in bolsonism as they recovered all the anti-communist language of the sixties and seventies. Brazil has two communist parties, the old partidao and the PCdoB, which are comparatively minor relative to other countries, and were smaller allies of the ruling PT. It will be all, less reasonable, to say that there is a “communist threat” in Brazil—contrary to what happened in Portugal, where they were in power, in France and even in Spain, where in certain regions they ruled. And even so, they directly regained the old anti-communist discourse. It’s also a matter of memory, and that has a particular meaning because they know it still works.

And that attack on universities isn’t also a new thing, is it?

All authoritarian states attack universities. All political formulas, and especially when they are transformed into a state, want to have their tools of formation and framing—and schools and universities are some of them—and they want to have, at the same time, a group of organic intellectuals who they manage to formulate, with a relatively erudite discourse and another, more open, turned to the masses, what is their ideology.

Before the far rights of the twentieth century attacked public education, the Church had already attacked public education in the previous century. The right-wing described the state of the way churches always did, accusing it of wanting to indoctrinate children and robbing families—after the churches would have wanted to teach children all about family, about gender identity, about sexuality, order and obedience. This dispute of hegemony through education between liberal, and then democratic, states, and churches is now reproduced by the far right that accuses all the social sciences, all humanities of having an overt ideological version.

The current government’s discourse in Brazil is that training must follow a utilitarian logic and that courses such as philosophy and sociology do not bring dividends for society.

In Portugal, until the end of the Salazarist dictatorship, there was no sociology, anthropology or psychology in the university. In all these cases there were only courses in the training schools of colonial officials. A utilitarian vision. Beyond, the first social sciences of the nineteenth century were born to help domination, to the knowledge of colonized peoples. It happened also in Brazil, it was to meet the indigenous people.

Suddenly, when science became an instrument of emancipation, the holders of order became unlike disliked by it and understood that it is sinful, blasphemous or, in its version in the 20th/21st century, militant. From Galileo it was like this. That is, everything that I research, interpret or conclude with a scientific methodology of the interpretation of reality is simply a discourse that underpins an ideology.

The Old Battle of Faith versus Science

For this religious far right, what counts is the sacred text, it is a description of nature made from the sacred, and that is immutable. That debate is thousands of years old. And so this attack is nothing new, and let’s also say that it is not exclusive to the far right.

But what is happening now is very serious: neoliberalism began to reverse an investment policy in education that had been coming since the 1940s, in several Western countries, and it enters into the discourse that the university has to be bound to the world of work—which is the m the company, the truth, that the university—and the school in general—must show its practicality, and that it is therefore a waste of public goods to train these people. And even worse if they’re a red side.

Is bolesonism a formula that can spread throughout Latin America?

I think it has some features that would allow it to be clearly expanded. Bolsonarism is, above all, a sum of nostalgia for the military dictatorship, with anti-corruption demagoguery and a political discourse focused on the moral question. On the purely moral issue, two of the classical right-wing leaders who came to power with the support of the far right, Silvio Berlusconi and Donald Trump, are men who cannot claim any probity in their professional tax and family life. This does not prevent them from making deeply reactionary speeches about the family in both cases.

Berlusconi said a speech about the family after publicly shaking hands with women. Trump is the same thing. Therefore, bolsonarism is simply the sum of that nostalgia of dictatorship, discourse on corruption—hence moralistic demagoguery—, which is then joined by a connection with the evangelical world. And if these three conditions existed in other Latin American societies, bolesonism could expand, it would be replicated. And I think there are very similar characteristics on the Venezuelan, Mexican, Argentine and Chilean right, for that to happen.

What we do in Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Politician, receive benefits and support free journalism.#YoSoyAnimal

translated from Spanish: “Bolsonarism is the neofacism adapted to 21st century Brazil”

August 11, 2019 |