In San Felipe, Yucatan, a municipality of 2,000 inhabitants attached to Quintana Roo, they have been in conflict for at least four years over the subject of sea cucumber fishing.

On the one hand, the fishermen of cooperatives, who have been working in the area for decades. On the other, the poachers. His presence, according to the president of the Federation of Eastern Cooperatives, Pastor Contreras Aviles, multiplied for five years, when the exploitation of sea cucumber became widespread.

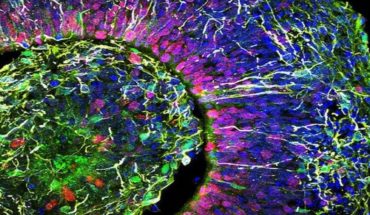

Sea cucumber is an animal that lives at the bottom, especially on coral reefs, and crawls aided by small tentacles.

Until a decade ago, no one was paying any attention to him in Mexico. But Asian customers arrived, who claim that this elongated bug, like a fat worm, has aphrodisiac properties, and wiped out the market, according to Alicia Poot, a researcher at the National Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Inapesca), a agency under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER) that is responsible for directing, coordinating and guiding scientific and technological research on fisheries in Mexico.

Prices skyrocketed.

A fisherman can receive between 90 and 120 pesos a kilo. But this animal is known as “sea gold” and its bill is multiplied along the way. A kilo in first cooking can cost 800 pesos. A first quality dry kilo, between 3 thousand and 4 thousand pesos. I. Badonotius, the species that is allowed to fish in Mexico, comes to cost $400 per kilo in Hong Kong, according to researcher Alicia Poot.

The arrival of Asian buyers satiated for sea cucumber fever. In less than eight years the fishmonger was practically exhausted, Pastor Contreras and Alicia Poot coincided separately.

Find out: Illegal fishing ‘exhausts’ octopus, grouper and sea cucumber in Yucatan

“Our seasons were excellent until the poachers got in. It was devastating. People are desperate.” Pastor Contreras Avilés is the President Federation of Cooperatives of the East. Fisherman’s grandson. Son of a fisherman. Father of a woman married to a fisherman.

Contreras explains that in the cooperatives there are about 800 fishermen associated, to which are joined by those who wait to be cooperative. That the trade union is old in San Felipe and that it is the workers themselves who protect its four ports: San Felipe, Ría de Lagartos, Colorada and El Cuyo.

Aware that the farm had caused the cucumber to almost disappear, last year they maintained a total ban. And the protection was successful. “Through Inapesca the studies were done. They saw that there were very high volumes of cucumber. But these bastards have taken everything,” he said.

According to Contreras Avilés, as soon as Inapesca announced that there would be cucumbers this year the poachers took the coast. “They fished him 24 hours a day, they came in day and night shifts,” he said. The fisherman claims that they have tried to speak to Conapesca and to any institution that has responsibility for the sea in Yucatan. But they haven’t gotten a favorable response.

Between 2014 and 2018, 5,736 tonnes of sea cucumber were caught, worth 178.86 million pesos, according to data from the National Commission on Aquaculture and Fisheries (Conapesca), the official Mexican body responsible for public fisheries policy.

This production was carried out only in the 15 days per year in which this catch is allowed. However, Alicia Poot, researcher of Inapesca specialized in this species considers that the figure could be up to three times higher because fishermen do not record everything they catch.

Admiral Héctor Alberto Mucharraz, head of inspections of Conapesca, recognizes that he has little to carry out his work: four agents for the entire Yucatecan coast, with more than a hundred municipalities and at least 10,000 active fishermen.

Animal Político also asked the Secretariat of the Navy and the Attorney General’s Office of the Republic, without obtaining an answer.

An attack with an engine and a fisherman without an arm

The history of furtivism is not new in San Felipe. Neither does the union that protects the coast. Its evolution shows the extent to which crime comes to impose its rules. At first, fishermen were doing rounds to monitor the bans and prevent access to the poachers. But these were sophistic, armed and won the game for humble fishermen, who have continued to fight in unequal conditions.

The height of the conflict took place four years ago. Until then, 50 boats were rounded to monitor the margins of the territory, which San Felipe shares with Tzilan del Bravo to the west, and the state of Quintana Roo to the east.

“Our surveillance system was to go 50 boats together, grab the poacher and hand it over to the authority. But they gave everything back to him,” Pastor Contreras complains.

Then he changed the type of illegal fisherman. If they used to be neighbors of adjoining municipalities who sneaked in to take over what San Felipe had protected, they were now workers hired by great entrepreneurs. Some of them, says Contreras Avilés, armed. Then everything got out of control.

Geovanni, one of the smug satered syllava, lost an arm when attacked with an engine. Someone was shot in the chest, too. Attacks on slobs, which were burned, were multiplied by the President of the Cooperative.

“Since then we have stopped doing surveillance actions. We got scared. Now there are between 600 and 700 poachers,” he laments. “They were no longer just fishermen, it was another kind of crime. There was a mob involved. There were guns and we were scared,” he says. “The poachers have outgrown us,” he certifies.

The problem, says the fisherman, is that the authority does nothing. It ensures that they have delivered lists with names, surnames, boats, license plates and, above all, buyers. None were arrested.

“People constantly complain and come to report, even though we are not the authority,” says Alicia Poot, Inapesca researcher.

He cites Tzilan del Bravo, San Felipe, Celestún. As he explains, the total ban implemented this year with the agreement of the permissives facilitated the recovery of the product. But this is affected by illegal fishing. “All efforts go to waste. It’s very serious,” he says.

Contreras Avilés explains that the price of sea cucumber has increased sixfold. So the poachers find a good excuse to keep acting. The fisherman believes that chasing the boats would be too expensive a job. “If there are 700 poachers, you’d need a fleet of 700 boats to chase them,” he says.

In its view, the authorities should act against the employers who purchase and distribute the product. The fisherman says that everyone knows who they are, that it’s “an open secret.” And yet they go unpunished.

Contreras Avilés speaks on behalf of hundreds of fishermen who believe that predation can end their way of life. He claims to have spoken with every authority who wanted to listen to them. But no one did anything. And he warns, “if they don’t act now they’ll have to do it when there are 11,000 poor fishermen out of work.”

What we do in Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Politician, receive benefits and support free journalism.#YoSoyAnimal

translated from Spanish: Conflict over sea cucumber hits the village of San Felipe

September 25, 2019 |