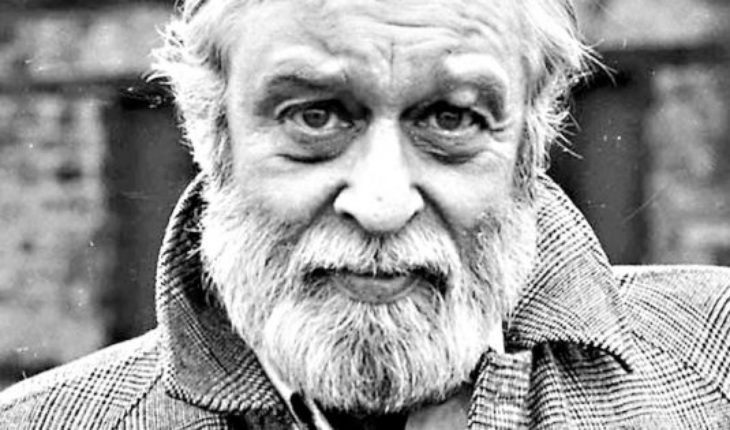

Richard Yates was born on February 3, 1926, in Yonkers, New York and died on November 7, 1992 in Birmingham, Alabama, at the age of 66. He wrote novels and story books and skilfully and blaively portrayed 20th-century American society. His first novel “Via Revolucionaria” (1961), nominated for a National Book Award, was one of his masterpieces and gave him recognition among critics and his peers. The plot was as simple as it was effective. It tells the story of Frank and April Wheeler, a young couple with two children seeking happiness in a suburb called Revolutionary Hill Estates. But their lives, monotonous and boring, don’t seem to take off. April tries acting but fails out flatly, as does Frank in her work. Then a recurring dream is reborn. To flee to Paris and remake their lives. Paris as the answer to frustrations. Paris as the hope that breaks at the end of the novel.

“Revolutionary Way” is heartbreaking. It is impossible to finish reading it and not to be a little hurt and moved. It is the dark side of couple relationships, those where we deceive and are deceived, where we make suffering and are wounded until the despair of the early morning. Debelfully beautiful, like all his literary output. His influence was significant in later generations and was reflected in writers such as Raymond Carver and Richard Ford, who rescued him from unjust oblivion. In fact his life was anything but happiness and he had to endure blows and loneliness with stoicism.

His work was discontinued and for a long time it was impossible to get his books. It had to be 16 years since his death and the motives may not have been the right ones. In 2008, “Via Revolucionaria” was taken to the cinema by Sam Mendes, with Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio starring in the lead roles. The film, correct to moments, failed to find the dense and hopeless tone of the novel. Characters too stylish and beautiful, overly condescending to the public. The opposite of Yates. However, the film put him back on the literary map and publishers re-edited his books. Life Lesson: The wrong reasons sometimes bring unexpected results.

In 1962 he released “Once Types of Loneliness”, a compendium of stories that took more than a decade to write. His characters, always insecure and about to send everything overboard, are involved in that silent desolation of routine, are normal people who reflect the Manhattan of the fifties, the opaque lives of office workers and taxi drivers, aspiring novelists, demanding teachers and women who refuse to say the name of their future son’s father. But beyond the plot, we see the boundary between the life we show and the life we hide.

Yates had published two brilliant books in two years, but that brief recognition would bring its consequences.

Let’s go to some details of his life. When he was 18 he enlisted in the army and was sent to France, where he became seriously ill with tuberculosis. On his return he worked as a journalist at the United Press and then at the Remington Rand typewriter factory. And as if an original and strange detail were missing, he wrote Robert Kennedy’s speeches until his assassination. Not bad all the way here. Then, like many writers of his generation, he moved to Hollywood and wrote several scripts for a living (including adapting William Styron’s “Lying in the Dark,” but the film was never shot). He also taught creative writing courses at the University of Iowa, Boston and New York, and so on. In that long period of time he was a lucid observer of that generation of confused Americans after the end of World War II. Yates intuited that the world would never be the same again. And he was right.

Then it looks like it sank into a dense swamp. Dark waters. But he didn’t stop writing. During the 1970s he would edit one of his great novels “The Sisters Grimes” (1976), in which he narrated, in a span of four decades, the story of two sisters who go through life for different defeaters, one more sophisticated and one more traditional, but both with the fate already cast. It contains one of the opening paragraphs of a book: “None of the Grimes sisters were meant to be happy, and as we take a look back always give sensity that the problems began with their parents’ divorce. It happened in 1930, when Sarah was nine and Emily was five.” Bright simplicity and elegance. Pure Yates style.

The wild wind that passes

Richard Yates was vainly by literary critics at the beginning of his career and forgotten in the end for being “repetitive” in his subjects or at worst for “having no style” or just writing about “losers”. They asked for novelty, as if art were a platform of Freaks where you always have to do something crazier and riskier, like Jackass, like a Johnny Knoxville of letters. But Yates did not let himself be intimidated and was true to his undaunted and raw view of the world. Nor was he kind to the readers, as if he wanted to evoke that kafka mandate where books must be axes that break the icy sea within us. And here’s a little caveat: reading Yates is difficult and touching. His books are like that inner rumor we feel when we lose something unrecoverable or when a slight memory, or a fuzzy face, disarms us in the middle of the workday.

In an age where the author and his media style seem to be more important than the depth of the work, United posers will never be defeatedYates took the risk and went down the less traveled path—that dark forest of children’s stories—and where there is no easy fame, no repeated flattery, no wines of honor with intellectual discourses that repeat clichés to nonsense. Yates, like a stylistic wizard, removes himself from the stories and lets the characters themselves be the ones who tell their lives and their misadventures, their failures and their despair. A form of command: the writer as a ghost who wanders like an invisible breeze over the main plot of his writings.

Richard Yates died at a difficult time in his life. In his last stage he published the book of Stories Liars in Love (1981), and some novels such as Cold Spring Harbor (1986), which were seen as minor works, but which contained the vision of a man who sought, until his death, the answers of the human condition in literature.

I honestly don’t know why these seemingly simple stories are going to go so deep. I’ve come to think that maybe it doesn’t matter so much what a story or a novel says, but the place that those stories take you. In the case of Yates it is a hostile place because there we find the loneliness in ourselves, that hidden treasure of our mistakes. But in his books, beneath that surface of the apparent, we find mercy, that parallel life that we live and that is born from the bottom of broken hopes. He was once asked about his work and said the following “has one theme, I suspect it is simple: that most human beings are inevitably alone, and there is their tragedy.”

The content poured into this opinion column is the sole responsibility of its author, and does not necessarily reflect the editorial line or position of El Mostrador.