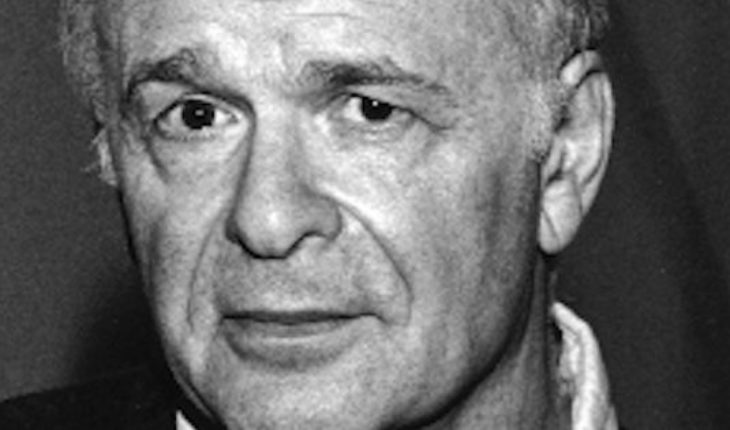

Stephen Dixon (New York, 1936-2019) lived and died as an unknown animal in the middle of an unexplored jungle. He died on November 6, 2019 at the age of 83 a product of Parkinson’s and until 2014 was practically a ghost in Spanish-speaking bookstores. Thanks to the Argentine publishing house Eterna Cadencia, two volumes of short stories were published that collected a careful selection of the author: “Streets and Other Stories” (2014) and “Ventanas y otros relatos” (2015), they became Dixon’s gateway to the reader in Spanish and its publication involved the discovery of a prophet of realistic fiction who for decades had been giving a twist to the classic structures of the story and the novel.

Reading Stephen Dixon for the first time creates a strange feeling. On the one hand, we have the situation of realism. A scene born from normality, from a couple’s breakup, from an accident, from a specific fear or fantasy. But then the plot suffers an irretrievable rupture. In their narratives there are always dislocations and leaks, changes of views, internal monologues that take us elsewhere. Dixon gives us a shortcut to what the characters think, as if the narrator eliminated the distance between character and reader. The American writer’s ability is astonishing. He is able to mix in a single story the desolation of a loss, the pathos that sometimes floods our inner life and the absurd humor of unlikely situations.

It is difficult to find any author to compare it, but perhaps it is arguably that he shares certain similarities with Thomas Pynchon (“The Rainbow of Gravity”), although the comparison is unfair to both of them because of the uniqueness of their works separately. Dixon’s narrative technique constantly plays with the experimentation he performs in each of his writings. Often such plot twists lead to a direct language and where dialogue (there is a tale called “He” particularly overwhelming where all dialogues are replaced with the word “said”) move the plot from one side to the other. We’re probably confused when we read some of their stories and that surprise is similar to breaking into our house and seeing a zebra in the living room eating sushi and watching an MTV reality show.

Perhaps inspired by Joyce and some French Oulipo experiments, his constant changes of view and the near-zero use of metaphor turn his narrative into an artistic object that makes us reflect on how our mind works in the face of obsessions and in the face of the daily ramblings we have on the subway, in the supermarket or when we wait for someone in a bar. Let’s face it. We have all planned to kill someone in our minds, planned cruel revenges and imagined extreme situations that are then diluted. The important thing is to have thought about it and assume that those ideas, even if we don’t like them, are inside us.

And that’s what it’s all about. His books are overwhelming, but we inevitably finished them. When we close the last page something has changed in us forever and it is not an exaggeration to say that the world will seem different, a little more threatening, but certainly more real and profound.

Success is the enemy

Stephen Dixon’s life doesn’t give us any more clues to his obsessions as an artist. It is recurring to see normal situations and common places that are transformed as they pass through the sieve of their old typewriter. He published in his lifetime more than thirty books (novels and short stories) and was a professor of creative writing at John Hopkins University in Baltimore for twenty-six years. He once lucidly noted that “success kills the writer.”

In 1995 he wrote “Interstate”, one of his most iconic novels and a unique and monumental book. The plot reflects Dixon’s constant fears: Nathan Frey is driving his two daughters when in the middle of the road he encounters two psychopaths who cause a catastrophe that will mark his life forever. Dixon takes Raymond Queneau’s idea of “Style Exercises” to the extreme, where the French writer briefly narrates the same event 99 times from different perspectives. Dixon takes that concept even further. The eight chapters of the novel are eight ways to tell the same story in new details. It’s like it’s eight novels about the same event in the same book. A task of a rarely seen magnitude.

The matter of which our dreams are made

One of his last books was “Late Stories” (2018), which chronicles the life of Philip Seidel, a writer and retired teacher who loses his wife. In the 31 stories connected to each other, which could be considered a novel, we see Philip trying to overcome the death of his companion. The book is built in a parsimonious and cumulative way with stories that give a diffuse picture of memories, with disjointed times that reflect the fragile of our memory and with that fantasy of “that would have happened if…” that the protagonist captures when he imagines a life without having known it.

The nostalgia of some “Late Stories” stories give way to small, heartbreaking scenes of absurd humor. The casual and transparent way of these narratives make us fall into the deep well of Philip’s mind and make us live the story as if we were the protagonists. And that is precisely what is valuable about the book, because it makes us aware of our own fears, of what disarms us, of what we do not comment on to anyone because by the time it is counted it already seems ridiculous.

Dixon has a particular talent that he developed in his work and was to reflect those details of life that escape: the finite of a memory or a look, a dream that we forgot in the morning, the second of an emotion lost in our memory and the fears that seem and disappear so fast that we’re not able to realize they exist. As you read your novels and stories, you feel, with relief, that existence is random and that we are not predestined by any divine design or pretentious simplifications of a stellar order.

Significant books come to us in strange and casual ways, such as loves, such as the unrepeatable nights we remember in solitude and as the nostalgia of rain in the middle of summer. The books that mark us come to us like those fuzzy streets we see in our dreams. I don’t know what Stephen Dixon’s epitaph will be or what the cemetery that holds his remains will be, but it’s possible that his grave is as normal as it is forgettable and that on his tombstone, full of dust, the grass will grow freely and without human intervention.

Read here the short story “Wife in reverse”

Read here the beginning of “Interstate”