Most people don’t think about death. This reminds us of death itself as he plays chess on the beach of The Seventh Seal, Ingmar Bergman’s best-known film. The day always comes, points out its opponent, when being on the edge of life one has no choice but to confront the darkness.

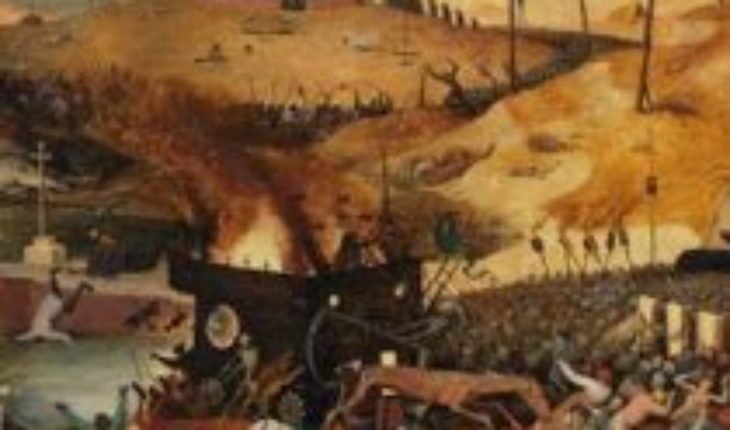

Throughout history there have been few more opportunities to reflect on the death itself as pandemics. Of these, the black plague has been the most devastating. Even today it permeates the image of the dark era that many have of the Medieval period, which Petrarch already called saeculum obscurum before the plague, for other reasons.

This pestis, which means exactly epidemic in Latin, took at least a third of the European population, reaching its peak of virulence between 1348 and 1350.

Yersinia pestis, plague-causing bacteria. Wikimedia Commons / CDCA mystery solved 500 years later

Today we know the origin of the disease, discovered in 1894 by Alexandre Yersin and Kitasato Shibasabur: a bacillus called Yersinia pestis, natural in rodents and transmitted to humans through rat flea. We also know that this bacterium has been the cause of three major outbreaks: the Justinian plague in the 6th century, the aforementioned black plague, and the most recent, the so-called third pandemic, which killed millions of people in China and India in the second half of the 19th century.

Let Boccaccio describe the ailment to us:

“And it was not as in the East, where to whom blood came out of the nose was manifest an inevitable sign of death, but in the beginning males and females were born similarly in the English or under the armpits, certain swellings that some grew to the size of an apple and others of an egg, and some more and some less, which were called bubbs by the people (…) immediately began the quality of the disease to be changed into black or livid spots that appeared to many on the arms and thighs and anywhere on the body, to some large and rare and to other small and abundant.”

The Italian writer devoted the first pages of El Decamerón to recounting the plague that ravaged Florence in 1348 and unknowingly explained the three main types of plague: bubonic, pneumonic and septicémic, caused by the bite of the flea or by the inhalation of droplets of Fl.gge.

Global contagion through trade

The text also gives us an idea of the eastern origin of the disease, which entered Europe on Italian merchant ships from Crimea and Constantinople. Although the primary focus is still a source of debate today, we know that from 1347 the epidemic spread unstoppably across the continent through commercial networks and travelers, inevitable vectors at a time when people were moving much more than they often think.

The black plague will eventually become a recurring disease and will be associated with war and hunger in what Julio Valdeón calls the trilogy of major catastrophes that make up the crisis of the fourteenth century.

Isolation and long-term effects

The ravages suffered in this first wave of the mid-14th will not be easily forgotten and although in time people will become accustomed to living with the disease, they will not fail to appear sources that remind us of their uncomfortable presence. For example, the Andanzas of the Cordoba knight Pedro Tafur, which tells us how difficult it was to access Constantinople by the Black Sea in 1437 due to quarantines and blockades.

We also have texts such as the dictionary of Georg von Nurnberg, designed for Venetian pupils of what we would today call a business school, where the basic vocabulary is provided to learn about pestilence and the dangers of the road in 1424.

Economic consequences and racism

The immediate consequences of the pandemic will not be health alone. The morbidity, curiously much higher in rural areas and with less population density, will mean the depopulation of many rural centres, the loss of incomes of lords and landowners and a crazy commodity inflation, which will be tackled with a rise in wages.

In many regions, the economy will take a generation to recompose and in many cases activity will change substantially. The switch to the telework of the times of the coronavirus had in this sense an equivalent in the expansion of livestock, for which there is not so much labor and in which abandoned spaces are taken advantage of.

As for its social repercussions, the epidemic will eventually crystallize anti-Jewishism in Europe.

It will be of little use for the Jews to get sick in the same way or for Pope Clement VI to condemn violence against them. Between 1348 and 1351 numerous communities, accused of polluting the waters and wells, will suffer pogroms and persecutions. In some cities, such as Mainz and Cologne, the Hebrew minority will be eliminated almost completely.

It seems relevant to recall these teachings of the past, at a time when the coronavirus arouses solidarity between neighbours, but sometimes also fear of the other and racism.

Pedro Martínez García, Professor of Medieval History, King Juan Carlos University

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original.