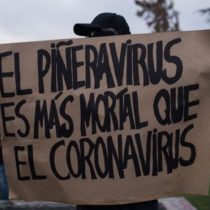

“Piñeravirus is more deadly than coronavirus.”

The phrase that alludes to President Sebastián Piñera, was read on one of the posters with which about 200 people returned to the streets of the city of Santiago to protest this Monday, April 27.

Water-throwing cars, tear bombs and harsh clashes between protesters and police again took Piazza Italia – or “Plaza Dignidad”, as some renamed it – the epicentre of the social outburst that broke into this South American country on October 18 last year.

Despite the health emergency, the image was repeated in other regional capitals, such as Antofagasta, Concepción and Valparaiso, where there were also barricades.

It was a symbolic day, because not only was the 93rd anniversary of Carabineros, the Chilean police institution, but also because it was remembered that a day earlier – April 26 – it was the original date scheduled for the realization of the plebiscite that seeks to change the Constitution inherited from the regime of Augusto Pinochet.

Since the arrival of the coronavirus in this country in mid-March, the agenda that sought to decompress social tension has come to the background and, with it, the referendum was postponed for October 25.

The intense protests, meanwhile, seemed to have ceased. Or, at least, that’s what it was thought to be.

However, they have slowly become more relevant, albeit in much smaller groups.

The reason behind it, its protagonists explain, is no different from that which motivated Chile’s “awakening” in October: the social discontent with the inequalities of the political and economic system prevailing in this South American nation.

In the Metropolitan region, more than 60 protesters ended up in detention on 27 April, Carabineros reported.” Coronavirus visibilized inequalities”

“We protest because the Chilean system is much crueler than coronavirus,” Paloma Grunert tells BBC Mundo, who has attended all the demonstrations since October and is behind the organization of some of the protests that have occurred in the middle of the pandemic.

For her, everything that initially led them to the “still current” street, such as inequity in wages and access to health and education, among others.

“There is inequality, injustice and constant support for entrepreneurs and economic groups,” he says.

A similar opinion is shared by photographer Cristóbal Venegas, who has also participated in the demonstrations.

“There is no credibility in government or political class. Social demands are in the skin,” he tells BBC Mundo.

Venegas claims that with the coronavirus they were “even more evident the problems of the people”.

“On the subject of education, for example, not everyone in this country has a computer, who can do classes online? The issue of health too; in some places there are no supplies, there are no inputs,” he says.

According to Cambridge University academic and social movement expert Jorge Saavedra, this last point is just one of the most important things that explain the “regrown” of demonstrations.

“What the coronavirus has done is make visible the structural inequalities that it protested at the time,” he tells BBC Mundo.

“If in Chile was once protesting health inequality, that has now been highlighted. The same has happened with job precariousness, where we have seen how fragile the system was. It was shown that the market did not solve the problems because now the market itself is asking the state for help,” he adds.

In the face of the emergency, however, The Chilean government has designed a series of measures to deal with the consequences of this crisis.

This is how an Economic Emergency Plan was created, which, with the injection of US$11,750, seeks to protect employment and support workers by giving liquidity to companies of all sizes.

It was also decided to strengthen the health system’s budget – it will be supplemented by 2% constitutional – to ensure that it has the necessary resources in the face of the pandemic.

On the other hand, an Employment Protection Act – which seeks to safeguard jobs – was established, and a $2 billion fund was created to protect the income of the most vulnerable (informal non-contract) workers, among other things.

During the demonstrations on 27 April, there were heavy clashes between protesters and the police. Anyway, this is a reality that doesn’t just hit Chile. In other Latin American countries there is a similar perception.

Due to the paralysis of the economy by quarantines seeking to deal with the pandemic, much of the population in the region has been affected by job losses or a decrease in wages.

This has given way to a deep social unrest that has been reflected in street marches, blockades and saucepans in countries such as Colombia, Mexico and Bolivia, among others.

“Coronavirus has exacerbated social differences,” Saavedra explains.

And, in the case of Chile, the academic states that the big demands that have been demanded since October “are still there”.

“There’s a political guy who still doesn’t feel heard. And that he believes that if he stops manifesting himself, he will go into oblivion,” he says.

Plebiscite: will it take place on October 25th?

Among these demands perhaps the most relevant and symbolic is the change to the Constitution that has governed Chile since 1980.

It is a petition that was heard loudly in most of the protests that took place in recent months in this country.

The lawsuit found an exit on November 15, 2019, when the Chilean parliament reached a historic agreement where a plebiscite was established to be held in April this year.

In it, Chilean citizens would be able to choose whether or not they supported constitutional change and the mechanism for the elaboration of a new magna letter.

However, the coronavirus changed plans and the referendum was due to be postponed by October 25.

But in recent days some political leaders have once again questioned its realization because of the pandemic.

President Piñera hinted that chile’s economic recession may be so great behind the coronavirus that the “perhaps” referendum should be discussed again. President Piñera himself said in an interview with CNN that “maybe the economic recession is going to be so big, that this is an issue that may be discussed again.” While several state ministers have indicated that everything will depend on the health reality of the country.

In conversation with BBC Mundo, Diego Schalper, deputy for the official National Renewal party, explains that it is important to take into account the legitimacy of the constitutional process amid the pandemic.

“Chile is in crisis. And we will have to look at the scale of the crisis in June or July to resolve whether they are the right conditions to make a plebiscite that has the necessary participation and legitimacy,” he says.

“You have to go back to work and carry out different activities, but that’s why it’s not possible to have a high-stakes voting day, to have a campaign like the one we all want to have legitimacy for this process,” he adds.

“Democracy doesn’t cancel elections for economic crises”

These approaches have not been well received by members of the opposition, who noted that it is “incoherent” for the government to propose a plan of “new normality” – which includes, inter alia, the reopening of shopping malls and the return to school classes – and, at the same time, to call into question the plebiscite.

“It’s worrying; elections are not cancelled or suspended in democracy because of economic crises,” says MS Gabriel Boric, part of the opposition Broad Front coalition, to BBC Mundo.

“There is a section on the right that has never wanted to change the Constitution and is looking for any excuse to try to install a debate around the subject. I want to be emphatic: we’re going to defend the constituent itinerary, even if they don’t like it,” he adds.

The parliamentarian says this is not a demand from politicians, but by Chilean citizens.

Chileans also participated in caceroladas against the Government of Piñera during the pandemic.” That social discontent that was expressed over the last few months is still present, cannot be hidden under the carpet, and we have to channel it institutionally,” he says.

Similarly, the president of the Party for Democracy (PPD), Heraldo Muñoz, told BBC Mundo that “the protest is still alive and questioning the plebiscite only does it alter the tranquility we need today to control the coronavirus.”

And Muñoz may be right because many of the demonstrators who today take to the streets to protest in masks say they are upset at an eventual postponement of the referendum.

This is the name of Cristóbal Venegas.

“The original pandemic is not the coronavirus. It’s the Constitution.”