Alicia is a home worker in Puebla, in a house where she is on a Monday to Saturday floor. His last day at work was April 18, but not because of the measures taken before the COVID-19 pandemic, but because a day later, he had to go to the hospital to give birth.

Despite being 9 months pregnant, her bosses didn’t tell her that if she didn’t feel bad, she had to keep going to work, and they suggested she take only eight days to recover from childbirth and come back—although she hasn’t. Not only that: last month he was paid less because he could no longer do all the house cleaning work. Of the 1,200 pesos he had for the six days of weekly work, which is less than two minimum wages, he was reduced to only a thousand, or 167 pesos per day.

Alicia’s employers (name changed for confidentiality), also ignored all warnings from health authorities that pregnant women are part of the population most at risk of contagion and that, even if they were not, they should have guaranteed them health measures and social estrangement.

Read: Full salary and allow domestic workers to stay at home, ask Employers to be asked

Until her last day at work, and pregnancy, she continued to leave the house over the weekend to take her breaks and return on Monday. She bought herself a bedside shop to get on the comb where she was on her way to her destination.

It is native to a village in the municipality of San Sebastián Tlacotepec, in the eastern end of Puebla, which borders Veracruz and Oaxaca, but rents a room on the outskirts of the capital of Poblana, in the colony Nueva San Salvador, where many migrants from Mazatecal communities of Oaxaca who are dedicated to masonry or clean houses live.

Alicia, 21, is taking over the new baby on her own, because the man didn’t want to take responsibility and disappeared as soon as she found out. She was treated in a public hospital where she was charged 2 thousand pesos for childbirth: the two-week salary, which is the time she has not been to work and therefore unpaid. Only one brother is supporting her and a neighbor, the son of another cleaner, who organized to collect donations and spread pantries among women in the colony who are in similar situations.

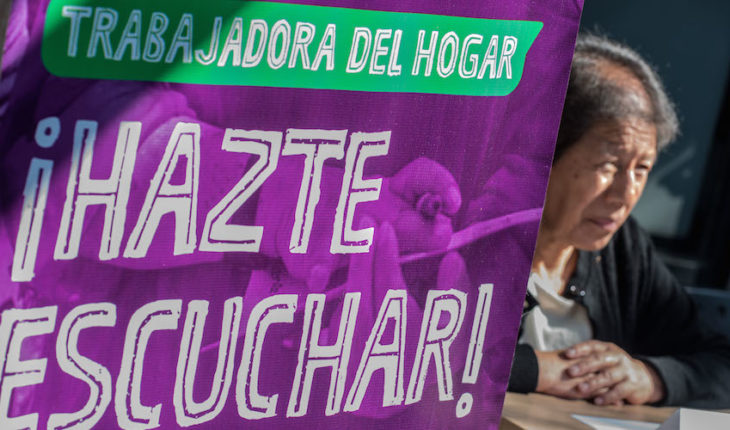

Like Alicia, many domestic workers are being victims of employers who do not respect their work rights, either because they are made exposed to their health to continue working, because they held them at home, or because they were told to stop coming during the health emergency, that they could eventually get their jobs back, but while they are not paying them anything.

“We have the report that many workers are being fired or rested without pay. Some continue to go to their jobs and it seems that with good security and security measures. Some are not allowed out of the houses in which they work, even if they want to leave, which is a very worrying situation of almost slavery,” says Marcela Azuela, of the organization Hogar Justo.

Find out: These procedures hold up the registration of domestic workers in IMSS

Locked up in the workplace

Unlike Alicia’s boss, Lola’s was concerned that she was leaving to go home and could contract the virus on her transfers, between the home of Tecamachalco, an upper-class area of the State of Mexico, and Cuajimalpa, where she lives. Then the employer proposed two weeks ago that you’d better be quarantined there with her.

Lola used to work in another house on Tuesdays and Thursdays, but when they started the health emergency there they no longer wanted me to continue to go. Losing that and as the coexistence with her boss of Tecamachalco is good, Lola agreed to stay with her.

“I didn’t think it was such a good idea, but seeing how this whole thing is… I thought about it, I was going to my house. I saw that people were scared and I thought I’d better stay, for my health,” says To Political Animal. “Until the contingency passes, I can’t get out. We’re cut off from everything.”

But Lola has two daughters, aged 15 and 23, and although they are no longer girls, she is divorced, so they are alone. It’s what bothers her about being locked up, although her boss has told her that if she wants to go see them she can do it but traveling by Uber, not by public transport.

What matters most to her right now, just because she’s the one who brings the money to her family, is not to lose her job and source of income for this contingency. He stopped going to another house where he also cleaned. And here, although he is now plant and unable to leave, he still gets the same 2 thousand pesos a week, 333 per day worked.

The academic at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology (CIESAS), Noroeste Séverine Durin, warns of the risk that clean-up workers, especially those who are planted, will be quarantined in the homes of their employers, because if clear agreements and schedules are not established, it may mean that they do not have rests and have their work increased without any pay rise.

Durin has specialized in the last 10 years in the study of domestic workers in Monterrey, Nuevo León, who are usually indigenous migrants from the Huasteca area.

In that city, Azuela learned of a case of an upper-class fractionation in which for safety, they would not allow domestic personnel to re-enter during the contingency, a situation that it considers to be discrimination. While Durin has heard of quite a few cases in which employers have preferred quarantine to include female employees.

“Just as there are women who have not been allowed to return to work, many have not been able to get out. Because we are faced with a type of employers who have a habitus as servitude; that is, people who are used to having cleaning staff in their homes and who have not learned since their socialization to clean a house, even to take care of certain things with their children, but not of all the parenting tasks,” he says.

Between dismissal and oversircy

Petra had been cleaning a house in Puebla for 15 years. But two months ago, because of the coronavirus, he ran out of that job.

“They were afraid because to transport us we have to use public transport. He told me not to go away, that we were going to wait two weeks, because he was concerned about my health, and mainly theirs, he told me… I said yes, to let me know, but it’s been two weeks, and then two more passed, and then until now and he hasn’t spoken to me,” he regrets.

She used to go four days a week, but it was never fixed: her boss would call her every time she wanted something, and she went. Gradually he had been increasing his salary and already collected 300 pesos a day, but received no compensation for the current situation.

“He didn’t give me anything. A little girl I recommended for a job, it was only two weeks, and she’s better paid half her salary, and that’s barely she came in! But this lady… I do not know… as my cousin says, they do have money but they don’t want to give. Because I say to him: if they go on a trip, they go on vacation, they buy clothes, because I say they do, I tell you. But I haven’t been called at all.”

Despite having been in the same house for so many years, as most domestic workers, she had no contract, nor had she enrolled in the pilot test of the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) to give social security, that in one year she has barely had less than 20 thousand members, according to data from the agency itself, of the more than 2 million workers of this type that are in the country.

Petra has two children and is separated from the father, so although her daughter asks her for money, she only gives her “for her tortillas,” she says. The youngest studies high school, but since he’s not having classes, they’re saving the expense of coming and going and eating out.

Her financial salvation has been her few savings and that an aunt of hers was operated on and then she is covering her in doing cleaning in the house of a foreign lord with which she has virtually no physical contact. He goes once a week and pays him 350 pesos, of which 50 spends entirely on taking three trucks one way to Angelópolis and three back to the colony Nueva San Salvador. And while he’s worried about COVID-19 contagion, he’s more worried about running out of money.

What to do not leave them in the helpless?

Specialists call for awareness of the plight of these women and to think that it is only fair that they too stop going out for their health, but that they do not run out of income.

“The call we make from Fair Home and from other organizations is that we be responsible with those who work in our house, take care of those who have cared for us doing the cleaning work and sometimes taking care of our children, of our older adults. That we are more committed and if we lower our pay, that is also happening or people are running out of work in their businesses, because if we have to get them down, they are lowered proportionately, not to fire them absolutely leaving them to their fate,” says Marcela Azuela.

Researcher Séverin Durin explains that we must start from the fact that we all have the same rights, so they have the right to health and must be sheltered at home with pay. It also calls for them at this very moment to register with IMSS, because “a person who has the economic capacity to employ a domestic worker can make the contribution that corresponds to him, which is minimal. It’s time to guarantee the right to health.”

In the case of plant workers, which are about 10% of the total, he stresses that if they are going to stay in the employers’ house, it is necessary to establish overtime payments, and not only that, but also to make agreements of working hours and rest days, so as not to fall into exploitation.

As hygiene work in homes is going to increase, it’s also going to increaseHe recommends not carrying their hand, then unloading them from other tasks: if you are asked to clean more, to do less care, for example. And to do so, it suggests that family members also take on more household chores, such as taking care of children who are out of school, because the employee cannot be behind them while cleaning and cooking.

Finally, provide them with bottle covers and gel alcohol if they are the ones who are going to be leaving the house to do the shopping. And ensure that they keep in touch with their families and loved ones, as they will be away from them.

To donate pantries to the Mazatecas household workers of the New San Salvador colony, in Puebla, such as Alicia and Petra, you can deposit to account 1164903072, CLABE 012650011649030729, on behalf of Hugo Carrera Guerrero with the subject “worker pantries”.

With information from Alberto Pradilla

What we do in Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Político, receive benefits and support free journalism #YoSoyAnimal.

translated from Spanish: Domestic workers are fired or forced to continue working

May 3, 2020 |