In the early days of August, José de los Santos Sauna Limaco died. He failed to cope with the complications caused by COVID-19. He was 44 years old and governor of the Kogui People, an indigenous community of the Sierra Nevada in Colombia.

The death of the indigenous leader was in anticipation of the International Day of Indigenous Peoples that is commemorated every August 9. For this year, the United Nations decided that the day should be devoted to the theme “COVID-19 and the resilience of indigenous peoples”. Today, the international body notes, “it is more important than ever to safeguard these peoples and their knowledge. Its territories are home to 80% of the world’s biodiversity and can teach us a lot about how to rebalance our relationship with nature and reduce the risk of future pandemics.”

But the COVID-19 pandemic threatens, above all, those who represent the memory and knowledge of indigenous peoples: the eldest people, grandparents.

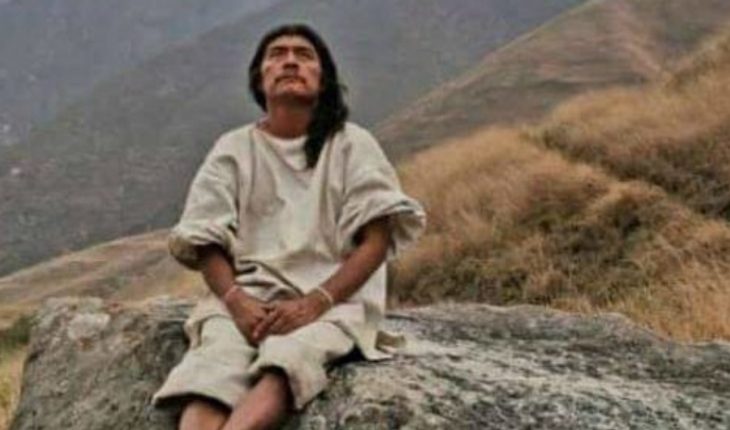

In recent months, the indigenous communities of Latin America have mourned the death of José de los Santos Sauna (Colombia), the leader Awajún Santiago Manuin Valera (of the Peruvian Amazon) or that of Claudio Centeno Quito, authority of the Sura nation in Bolivia. Their names are just some of those who have passed away.

Santiago Manuin (second from right to left) and other Awajún leaders during the trial for the conflict in Bagua. Photo: CAAAP.

With this pandemic “millions of ancestral knowledge about the jungle have gone. Knowledge that can save the world, knowledge about plant management, ecosystem management that no scientist knows. For us the greatest pain is that a whole history of our peoples is going away”, explains José Gregorio Díaz Mirabal, who belongs to the Wakuenai Kurripaco people, originally from the Venezuelan Amazon, and who is in charge of the Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA).

The “older”, the ones who are most vulnerable to COVID-19,” says Ruth Alipaz Cuqui, of the Amazonian community of San José de Uchupiamonas in Bolivia, “are our libraries, our knowledge library that has to be passed on to the next generations. The death of an old man means a great deal of loss to indigenous peoples.”

Gregorio Díaz Mirabal points out that in addition to the sages who are taking COVID-19, we must not forget the indigenous leaders and defenders “who have left because they have been killed” for defending the environment and its territory. Only the recent Global Witness report notes that of the 212 environmental and territory defenders killed, 40% belonged to indigenous communities.

José Gregorio Díaz Mirabal, who is in charge of the Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA).

Read more COVID-19 confinement precipitates deforestation in Asia and South America

“Structural” pandemic

In the Amazon basin, a territory inhabited by 511 villages and distributed in nine countries, there is a state of alert. Indigenous communities not only face the advancement of mining, oil projects or deforestation for the expansion of industrial agriculture. Now, for just over five months, they have the COVID-19 pandemic before them.

Until 4 August last, the Panamanian Ecclesial Network (REPAM) and the Coordinator of the Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) documented 34 thousand 598 cases of indigenous people infected with COVID-19 in the region. In addition, there had been 1,251 deaths.

“Almost 15 indigenous brothers are infected daily in the Amazon basin. Every day five or six siblings die… There are villages that have 40 inhabitants, if that comes the COVID the village ends”, highlights José Gregorio Díaz Mirabal, of COICA.

Lizardo Cauper Pezo, president of the Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle (AIDESEP), mentions that this pandemic further undressed the historical abandonment, the neglect that there is towards indigenous peoples.

For Gregorio Díaz, indigenous peoples live in a situation of “structural pandemic”, because there is a systematic violation of their rights.

President of the nationality siekopai Justino Piaguaje (in the center) together with siekopai leaders in Lagartococha in the Amazon on the border between Peru and Ecuador. Photo: Amazon Frontlines.

Read more Peru: indigenous people in isolation and initial contact fenced by COVID-19

“Indigenous peoples have always lived like this: abandoned to our fate,” says Bolivian indigenous Ruth Alipaz Cuqui, of the National Coordinator for the Defense of Indigenous, Native, Peasant and Protected Areas (CONTIOCAP). And it offers a fact that allows us to better understand his words: in Bolivia, where mitits inhabitants are indigenous, it was until last July 8 that it was announced that it would have an aid plan for this population.

In other nations, such as Mexico—where 65 indigenous languages are spoken—it was until May 21 that guides were held for the care of indigenous peoples; i.e. these documents were published three months after the country recorded its first cases of contagion.

In this country, as of August 6, official figures reported 825 indigenous people who died of COVID-19. Yucatan, Oaxaca, the State of Mexico, Quintana Roo and Puebla are the states where the most deaths of people speaking of some indigenous language have been reported.

A member of a brigade performs a COVID-19 test on Waorani leader Nemonte Nenquimo. Shell, Pastaza. Photo: Mitch Anderson / Amazon Frontlines.

Read more “This pandemic is taking away our wise men”: the tragedy of COVID 19 in the Awajún and wampis peoples

Indigenous organization: one step forward

In the Amazon basin, Gregorio Díaz explains that, thanks to the protocols they put in place, the blow to COVID-19 has not been greater. The communities activated the Indigenous Guards, indigenous health commands were established and an Emergency Fund was promoted through the Amazon. From the same indigenous organizations, such as COICA, “many communities have been addressed; in many of them the state has not yet arrived.”

One of the actions that attracts the most attention is the one that takes place in Colombia, where 115 indigenous peoples are officially recognized.

In the South American country, the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC) – which brings together 80% of the country’s indigenous organizations – adapted the Territorial Monitoring System, created in 2013, to monitor the pandemic in indigenous territories and have data that allow them to take containment, care and reporting actions.

Seven years ago, the communities that are part of THE ONIC looked at the need for accurate data on indigenous territories. This is how they began to georeference communities and shape what is now the Territorial Monitoring System, explains its coordinator Wilson Herrera.

The system has been used to monitor issues related to land rights, human rights and environmental rights. When COVID-19 arrived on Colombian territory, ONIC decided to create a special module to monitor the pandemic in indigenous territories.

The Territorial Monitoring System began with a containment stage and are now at the attention stage, where “we use information for decision-making: if we see that in any area there is an outbreak, then guidance is given to the indigenous authorities to strengthen territorial control, community and family controls”.

The Kogui village of Colomibia. Photo: Ombudsman’s Office.

Read more Indigenous peoples in Mexico: how to deal with an epidemic, discrimination and the historic abandonment of the state?

With this Monitoring System, ONIC has been able to identify that COVID-19 is already present in at least 60% of indigenous communities. In addition, it has documented 7,000 cases of infection and 243 deceased people. “Every ten days the number of cases we encounter is doubled,” says Wilson Herrera.

“If trends continue as they go, if we fail to contain, if we fail to articulate with the government, we identify that by the end of the year we will have a humanitarian crisis in the case of indigenous peoples,” warns Wilson Herrera, who also stresses that the government has left indigenous peoples in an orphanage.

In addition to using data to save lives, another objective of the monitoring system is to “systematize the history of the pandemic in indigenous territories. We’re going to be able to tell the world what happened to the pandemic.” Wilson Herrera points out that it will be able to show what the Colombian government’s action was in the attention of COVID-19 in indigenous peoples.

Indigenous ritual. Photo: Juan Gabriel Soler, Gaia Amazonas Foundation.

As in other Latin American countries, Herrera explains that in the face of government indifference and abandonment, indigenous communities are turning to their forms of organization and traditional medicine.

At ONIC, they are also developing a system that allows indigenous people to conduct self-assessments and identify symptoms of COVID-19 early.

These actions are carried out thinking that “at least 260 thousand families do not have the possibility of reaching a health center, because they are more than ten hours’ drive from a medical unit”.

The Territorial Monitoring System also prepares a “own economies” module to begin documenting data on food sovereignty and native seeds, as well as an ideto identify territories that could have the greatest impact on climate change scenarios.

Indigenous women collect food in their shacks. Photo: Stefan Ruiz, Gaia Amazonas Foundation.

Read more Bolivia: indigenous people fear COVID-19 advancement by workers of hydrocarbon companies

Extractivism and projects that don’t stop

For the deaths caused by COVID, but also because during the pandemic “extractivism has been brutal; legal and illegal gold mining, oil exploitation has not stopped and continue to grant concessions without prior consultation”, Gregorio Díaz does not hesitate to use two words to define what is lived in the Amazon basin: “ethnocide” and “ecocide”. He emphasizes it with a phrase: “We are in a situation of extreme health and environmental catastrophe.”

Ruth Alipaz explains that, in Bolivia, the government has allowed extractive activities, such as oil exploitation, to continue in the Chaco region. Mining also did not stop in the Bolivian Amazon and this has caused, according to Alipaz, that indigenous populations that are in initial contact, such as the Yuquis, “are already beginning to register contagions”.

In Mexico, projects like the so-called Tren Maya also did not have quarantine. While much of the country’s economic activity was paralyzed by the health emergency, the federal government flagged the way for construction of the train to begin.

The mayan train’s stroke involves passing through four states with a high presence of indigenous population: Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo; a region that has seen swine farms multiply, where the Mayan forest has also been deforested to make way for African palm or soybean farmland and where tourism developments have ended with mangrove areas.

International Indigenous Peoples Day “means raising your voice and denouncing the megaprojects they are trying to promote on the Peninsula, which they will actually do is destroy the territory,” says Wilma Esquivel Pat, a Maya native, inhabitant of Felipe Carrillo Puerto, in Quintana Roo and vice president of the U Kuuchil K Chibalom Community Center and a member of the indigenous government council.

Roads in the Mayan area of Campeche. Photo: Thelma Gómez Durán

Read more Ecuador: COVID-19 reaches Waorani Indians as other peoples face new problems

It seems that no matter what country they are in, when it comes to boosting mining, oil extraction, agribusiness or a train, indigenous people in Latin America hear the same arguments. Ruth Alipaz, en Bolivia; Lizardo Cauper, in Peru, and Wilma Esquivel, in Mexico have heard how megaprojects are justified with words like “development” or “sources of employment”.

“From the institutions they say that these projects are going to give work, but they don’t say everything we’re going to lose; we’re going to lose the land… Our existence is linked to the earth, the cosmos, the water, the stones. How are we going to maintain the bond with the earth if they destroy it, if they end up with our way of existence?” asks Wilma Esquivel.

Without the land, without the milpa, without the jungle,” Esquivel says, “the word “Maya” makes no sense, it just becomes a term that is “commodified”.

The vision of development that is imposed “from top to bottom”, explains the Peruvian Lizardo Cauper, has had consequences on indigenous peoples: “they have impoverished us by killing nature”.

And he talks about what has happened in Peru with oil extraction, mining and illegal exploitation of timber. His words can be applied to any country in Latin America: “They have left a photograph of the rights violated; indigenous peoples without basic services, with contaminated water, with polluted rivers and soils, with diseases.”

The Sapanawa village, which lives near the Brazil-Peru border, was contacted in 2014. Isolated indigenous peoples like them now have a high risk of coronavirus. Photo: © FUNAI / Survival International.

Read more Colombia: COVID-19 soars in Leticia and frightens the indigenous peoples of the Amazon

Indigenous and Nature Rights

As of Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization (ILO), the rights of indigenous peoples have been recognized in various constitutions and laws of Latin American countries. But, in the last 30 years, “the vast majority of the achievements we have had have been legal and very few territorial: our rights remain violent, our territorial spaces in the process of destruction”, says Gregorio Díaz of COICA. The leader further points out: ILO Convention 169 “seems like a beautiful poem for indigenous peoples, but it is not fulfilled. No country respects it.”

Not even those countries whose governments “called the propertyIndigenous erfil,” says Ruth Alipaz: “In 2009 the Plurinational State (in Bolivia) was born and we believed that it was consolidation, that plurality was represented by us, the indigenous peoples. That’s become mere political discourse. The Constitution has been shelved.”

He says that with the transitional government in Bolivia, they did not change things either: “No decree was annulled of what we call ‘incendiaries’, because they are the ones with which the burning of more than 5 million hectares of the Chiquitaine forest has been legalized, to continue the policy of boosting agribusinesses”.

Even indigenous peoples also have limited political rights, says Ruth Alipaz. In the case of Bolivia, a law was passed that no one can participate in political life if it is not through a party.

Fire-ravaged area in Bolivia’s ‘mbi Guasu.” Photo: Native

Read more Court forces Ecuador government to protect indigenous Waorani population during pandemic

All governments, says Lizardo Cauper of AIDESEP, still do not recognize in the facts “spiritual, cultural values, the rights of indigenous peoples”.

Against this background, Gregorio Díaz proposes that in 2020, the International Day of Indigenous Peoples should mark the beginning of a new phase of struggle for communities. A struggle in which rights cease to be dead letter. And to do this it is necessary that, among other things, a “new economy that respects the jungle, that respects the rivers, is promoted… a new economy that pays for the trees to be preserved, so that there is healthy food in the territories, that respects the rights of communities and nature.”

Indigenous peoples, Lizardo Cauper says, “we want our own economy, our own education, health and intercultural justice. We want to exercise our right to self-determination.”

Organizations that are part of COICA and others in the region are driving a moratorium on extractive activities in the Amazon, filed legal action against governments such as Brazil, and will begin a global campaign that will have as its main issues climate change and the protection of the Amazon. This campaign kicks off on this International Day of Indigenous Peoples and will run until September 22, as part of World Climate Week.

For many indigenous peoples of the Amazon it is necessary to travel more than 24 hours in a motorized canoe to reach the nearest hospital. Photo: Mauricio Torres / Mongabay.

Read more Peru: Indigenous leaders report 58 COVID deaths 19 in Ucayali shipibo konibo communities

Indigenous stronghold

Although different geographies live, Wilma Esquivel, Lizardo Cauper and Ruth Alipaz, Gregorio Díaz and Wilson Herrera agree that the pandemic has not only further undressed the abandonment faced by indigenous peoples. It has also been a detonator of reflections and strengthening its capacity for collective organization.

In Mexico, for example, Wilma Esquivel says that during the months of health contingency, many young Maya who worked in cities and hotel areas returned to their communities and have returned to work in the milpa, have returned to learn from the elderly. “Grandparents say those who left and now returned are remembering who they are.”

Peru’s Lizardo Cauper comments that this pandemic has given them strength to continue defending their values, their medicine and ancestral knowledge. Bolivian Ruth Alipaz recalls: “As indigenous peoples we have survived other pandemics, in other times, under the same conditions that we are now facing.” So, he points out, they’ll keep giving the fight.

Wilson Herrera comments that, for the last four years, the indigenous communities that make up the ONIC decided to start a process to “strengthen our language, our crops, our medicine, our traditions… The pandemic came and we were already in that process. The elders and the wise men managed to see that was coming.”

Here you can check the page of Mongabay Latam

What we do in Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Politics, receive benefits and support free journalism #YoSoyAnimal.

translated from Spanish: By COVID, ancestral knowledge has been lost

August 9, 2020 |