In 916 King Charles III of France, nicknamed “the simple”-meaning “honest”- received a gift that greatly pleased him.

Julius of Berry, from Antwerp, had given him a fountain full of ripe strawberries from the forest; as a reward, the king gave the family the name “Fraise” (strawberry, in French).

800 years later, another king of France, Louis XIV, was concerned that his country was not doing well in the Spanish War of Succession and feared that a peace treaty would leave the court of Versailles without access to America’s riches.

In 1711 he decided to send a spy south of the New World to collect information. The chosen one turned out to be no less Amedée Francois Frézier.

The surname had changed a little, as the family had settled in Scotland in the Middle Ages, as part of the entourage of the French ambassador, and there he became Frazer; back in France, he remained in Frézier, but Amedée was a descendant of Julius, the one who had given strawberries to Charles “the simple one”.

And, in one of those curious coincidences of history, his trip to South America would forever change that delicacy that pleased the monarch so much.

Spy merchant

Frézier tells in his account “A journey to the South Sea and along the coasts of Chile and Peru, in the years 1712, 1713 and 1714” that he pretended to be a merchant seaman in order to carry out his espionage mission without raising suspicions.

And he accomplished his task without major problems.

But the most momentous result of his journey would not be evident until a few years later and resulted from his encounter with something that captivated him as he passed through Mapuche lands: a plant that the natives called quellghen Or kellén.

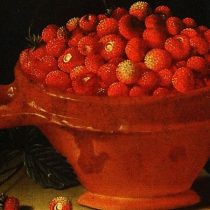

“They grow whole fields of a different strawberry species than ours by the more rounded, fleshy and very hairy leaves.

“Its fruits are usually as big as a walnut, and sometimes like a hen’s egg. They are a whitish red color and a little less delicate than our forest strawberries.”

Let’s make a parenthesis to talk about these peculiar fruits and understand why the French spy was so close to those that the Indians had been growing for about a thousand years on that strip of land between the Andes and the Pacific.

(Strawberries)

Because although they look like berries, strawberries are actually the thickened receptacles of the plant flower, which is from the rose family.

Roses and strawberries are from the same family.

The “seeds” that dot the surface of the strawberry are actually achenes, a type of dried fruit produced by some plants in the wild where the mature ovary contains a single seed.

Its generic name, Fragaria, is derived from fragum, fragrant, for the aroma of fruit.

It is difficult to establish the origin of strawberries as endemic species have been found in almost every place in the world other than Australia, the lands east of the Andes, the Middle East and Africa, (although there is such ancient evidence of their cultivatin in North Africa and the Middle East that they are perhaps also native to those regions).

Globetrotters

Studies of their genome have revealed an interesting story: it turns out that European strawberries are diploids, so they have two sets of chromosomes in their cells – like most species, including humans: one from the father and one from the mother.

But American strawberries are an octoploid, i.e. they have eight complete copies of the genome that were provided by several different parental species.

A beautiful and tasty genetic curiosity.

Researchers think they may have traveled through Asia (where species with 4 and 6 sets of chromosomes are found) and reached the west coast of North America through the Bering Strait 1.1 million years ago, where a hybrid was created with the existing species.

It is believed that from there the birds brought these octoploid strawberries to what in the very distant future would be Chile and Hawaii.

The thing is, by the time humans appeared on the planet, there were already wild strawberries of many types all over the northern hemisphere and on that land in the south where picuches and Mapuche would tame and grow them for centuries before Frézier arrived.

Your souvenir of the trip

Native Europeans had taken longer to move wild strawberries to gardens, some for their ornamental value.

We know that in 1368 King Charles V instructed his gardener to plant 1,200 strawberries in the royal gardens of the Louvre in Paris and that in 1375, at the Chateau de Couvres of the Dukes of Burgundy there were four apples dedicated to the cultivation ofand strawberries, so appreciated by the Duchess that when she went on a trip, they sent them to her.

Cultivated or wild, Europeans were fascinated by strawberries.

But, although their color and taste were intense, they used to be small.

That’s why Frézier got so excited to see what would be called Frugaria chiloensis and could not resist the temptation to take it as Souvenir five of those plants.

What I didn’t know was that all the ones she wore were feminine, so when they got to France, they didn’t fruit.

Et voila!

The Fragaria chiloensis it had not been the only American strawberry to cross the Atlantic and complete that round the world started millions of years ago to meet its diploid premiums in Europe.

It is not well known when but the Virginian Fragaria, which grows in the U.S. and Canada, it had also arrived in France but, although it stood out because its color was so deep that they called it “scarlet strawberry” and its flavor was intense, it was also small, so it had not gone from being a curiosity.

When it looked like Chilean strawberries were going to run just as lucky as The American strawberries, a young botanist began to discover why the plants Frézier had brought did not bear their fabulous fruits on Parisian soil.

In 1764, Antoine Nicolas Duchesne presented King Louis XV with strawberries so large and beautiful that the monarch commissioned an illustrator to paint them.

Duchesne, who was 17 at the time, had managed to make Chilean plants bear fruit by pollinating them with the European species Fragaria moschata, but the seeds of the strawberries he sent to the king were not viable.

Intentionally or not, gardeners in Europe began producing larger strawberries.

Although he continued to study these plants, and intuited through them concepts of evolution that Charles Darwin would need a century later, he failed to understand the problem until 1766, after noting that gardeners and farmers in Europe had managed to produce large and aromatic fruits.

Duchesne was the first to understand what had happened: intentionally or not, they had planted Virginia strawberries near Chilean strawberries, stimulating the latter to produce fruits, and the seeds of those fruits in turn produced vigorous and resistant hybrid plants.

The French botanist named the fruits of these hybrids Fragaria ananassa, or pineapple strawberry, because – according to him – “the perfume of the fruit is very similar to that of pineapple”.

These strawberries, the size of their Chilean mothers but with a darker red color and a more pronounced taste, were taken over the world.

That’s no exaggeration: it’s highly likely that each and every strawberry you’ve ever eaten is descendants of those kellén that the Mapuches cultivated.