“In the mountains you are exposed to risks and there are moments of great tension. One learns to be preventive, to react to difficulties by managing problems. Summiting is difficult because tiredness and fatigue always call to abandon. Then you have to appeal to the will and discipline.”

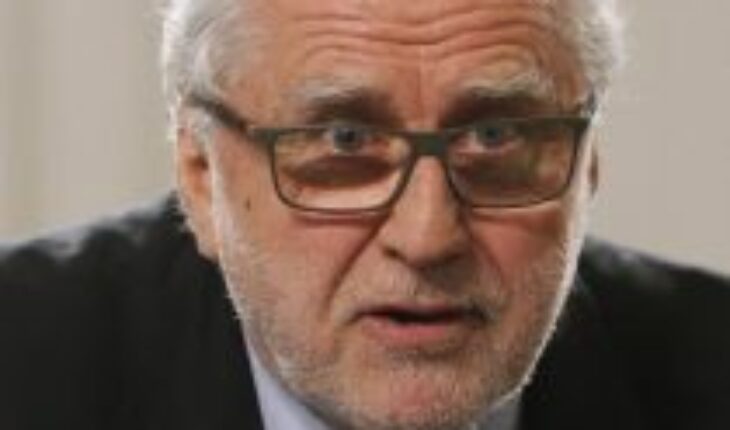

The phrase was formulated by the current president of Codelco, Máximo Pacheco, in an interview he offered to the UC University Magazine in 2019, an opportunity in which he referred to one of his passions: mountaineering. But the species may well reveal the emotion of these last days when the economist, academic and businessman, had to walk on the ledge, like a tightrope walker to carry out a political decision such as the closing of Windows and unleash at the same time one of the most complex problems that a government can be faced: enter a collision course with the copper workers, who if they had maintained the mobilization would have caused devastating damage to the administration of Gabriel Boric.

“What Máximo Pacheco did is something that requires decision, not only because he must negotiate with a world very difficult to deal with, but because the government parties and local authorities were not very clear in giving him support,” says sociologist Eugenio Tironi, who is among the defenders of a figure capable of issuing lights in terms of management, but at the same time it is capable of casting a long shadow on various issues, all of them quite controversial, which is why some see it as a true epitome of the neoliberal technocracy of the Transition.

Some of those consulted for the preparation of this note agree on a trait of his personality, one that may well help us explain his decision to break this true taboo that is, in short, to promote the closure of a Codelco facility, something that would predictably trigger the discomfort of the Codelco union organization. “Máximo Pacheco has a predilection for complicated subjects. He is stimulated by the challenge of facing what nobody wants to face,” says who was a close collaborator of the current president of Codelco when he served as Minister of Energy, during the second government of Michelle Bachelet. And boy is this matter of the Ventanas foundry complicated, according to Tironi: “I am a window and the plant has been giving problems for many years. When I was in government, in 1990, there has already been talk of the need to close it… But no one ever dared to do it!”

His former collaborator in the Ministry of Energy knows what he is talking about: Pacheco was responsible for pushing the transformation of the energy matrix in a context in which entrepreneurs were refractory and skeptical to adopt new technologies in generation. It was not the only thing: the challenge had the additional component of confronting communities that, with a learned distrust already difficult to dismantle, zealously protected the integrity of their territories in the face of unprecedented energy projects.

“It has that thing of making highly complex, very unpopular decisions. Like Ricardo Lagos saying no to the United States (for the invasion in Iraq), or like when Lagos himself confronted the microbus entrepreneurs to push a new transport system, something that nobody dared to do, “says his former collaborator.

“He has great capacity for work and articulates the teams well, and that articulation is achieved based on the stick and the carrot. It is true that it squeezes in the fulfillment of the objectives, but it is also good at encouraging. He himself says, ‘Tell the donkey that he has strength.’ Overall, I would say you have a strategic understanding of the issues,” he adds. He is, in short, a man of an executive nature who struggles to impose his terms in the negotiation, an issue that often bothers those interlocutors who commune with a horizontal culture. “He is very skilled at negotiating. In an indigenous community they baptized him ‘El Pachueco’ for his friendly but aggressive style,” adds the former collaborator.

“He has his trusted people and tries to take them everywhere, as he tried to do with Daniel Gómez (journalist) and Gabriel Sepúlveda (public administrator), who are his orejeros … but who does not have them! He made that team when he came to the Bachelet government. The first was his head of communications and the other was the chief of staff, and it transpired that he tried to take them to the company as staff in charge and as members of the board. And that is impossible,” adds the advisor, situacAn ion that can graph the confidence that Pacheco has in his media.

Another trait highlighted by those who have known the entrepreneur closely is his perseverance that may well pass for stubbornness. A source who was part of the campaign team of the failed presidential candidacy of Ricardo Lagos – a cast that was led by the current president of Codelco – points out that Máximo Pacheco “has a lot of faith, and perhaps that confidence in himself may be a little excessive. For example, he thought he could lift Lagos’ candidacy and there was no case. Lagos never scored. I think that is one of his great failures, because he did not know, I think, to read the signs of the new times. Nor did he do well within the (Socialist) party promoting that candidacy. Few squared with her and it seems to me that she resented it.”

Daniel Sierra Parra, who served at Codelco as vice president of Human Resources, highlights the skills of the socialist militant as a driver of organizations as complex as, by the way, the state copper company. “Máximo Pacheco is a great professional and very demanding with his teams, with a great sense of objectives and goals.” Tironi adds: “Pacheco is not new to Codelco. Already in 1990 he assumed the most difficult task, which is to take over the executive vice presidency of Operations. And for that you also have to have cojones, “he emphasizes.

Less conceptual is the opinion that the president of the National Federation of Petroleum Workers, Nolberto Díaz, has about the “Pacheco style”, whose time as president of ENAP between 2014 and 2016 qualifies as a “disaster”, something that accounts for “more than ten reports from the Comptroller’s Office that support our criticisms of their work”.

“Pacheco, at least for the workers, is the worst thing that has happened to ENAP,” he adds. “Three or four times we met, we even received him at the union in Concón, in a naïve gesture on our part that I regret. I have the worst impression of his business management and his way of acting because he moves by his personal agenda and is capable of everything. It is not credible for us oil tankers. Here we learned about his dark actions and he is not welcome,” says the ENAP union leader, who described Pacheco’s arrival at the copper company as “a mistake” by President Gabriel Boric.

Not only the excess of confidence and his excessive personalism question those who have accompanied him in his different challenges. “He also has this excess energy that leads him to get into everything, and that can make him uncomfortable because he can meddle in competitions or matters that are not his own. It’s not that micromanagement in order to take on the tasks of his subordinates in person, but it’s that kind of person who is always on top, asking, and that can be a bit exhausting. And because he’s an executive person, of doing things, sometimes he can stop talking because he concentrates on doing things, and that in political matters can be complicated because you interpret that you make decisions without consultation.”

His former collaborator in the Ministry of Energy recalls that “Pacheco has the same this average employer thing, but kind. It’s a dynamo of energy.”

The continuity of the transitional culture?

“Whenever I feel fatigue or tiredness in the fulfillment of a goal or objective, it inspires me to remember the idea of persevering and knowing that the goal is to make a summit. It helps me to do it on the basis of a collective effort of motivation. The great tasks are done as a team and only with that spirit can we continue to move forward,” Pacheco said in the aforementioned interview, which shows his determination in the face of challenges that seem impossible.

By the way: some say that Máximo Pacheco is a transversal man. “I think he ranks very well in any position that they put him. It does not matter in which ministry or in which public company, because he does both: he is a politician and he is a business manager,” says the source who was part of Ricardo Lagos’ campaign team about Máximo Pacheco.

“He likes difficult things. But when I learned that he had messed with the workers of Codelco, I still doubted that he could advance a little, because nobody dares to mess with that world, “he says later about the risky bet of the economist, who found in mountaineering one of his main passions, to the point that on many occasions he has highlighted two milestones in his amateur sports career, two objectives that he considers as valuable as his achievements in political and business matters: having reached the top of the Ojos del Salado volcano and Mount Vinson in Antarctica.

“At work it’s like that, very pushing, persevering. He is like every mountaineer: this of the will, of throwing him in front … Very much of that self-help discourse in terms of convincing yourself that it’s possible to move forward when no one else sees it possible to take that step. Now, if they tell me that he himselfor he’s going to lead the new foundry project, I think so. Maybe he’s already at it,” the source says.

Nolberto Díaz, union leader of ENAP, believes that the future of Codelco is not very bright under the leadership of the socialist militant. In his opinion, it is enough to see what happened to the state company while it was in charge. “It is the darkest and most corrupt time that the state oil company has lived,” he says.

“In his administration appeared corrupt and millionaire contracts without justification, most assigned directly between roosters and midnight. We have the issue of the change of logo, the unnecessary change of corporate building … In mid-2014 he changed the historic helicopter contract with the COMPANY DAP to give it to the company Ecocopter of Eduardo Ergas. On top pushed the New Era thermoelectric plant of Mitsui in Concón. Let’s not forget that Pacheco defended declaring the Alto Maipo project of ‘national interest’ to ensure its financing through ENAP”, a maneuver in which, as Díaz recalls, he worked side by side with Marcelo Tokman, who was general manager of the oil company until 2018, the year in which he resigned to go to work as a director at AES Gener. “Let’s not even talk about their anti-union practices, etc.,” adds the workers’ leader. “In his period ENAP ended up increasing its indebtedness by 1,300 million dollars,” adds Díaz in his lapidary evaluation of Pacheco’s work.

Born in 1953, this economist – trained at Saint George College and the University of Chile – has served as a bridge between Chilean progressivism and the business world, one he knows inside out, as he has been director of some such as Lucchetti, Falabella, AFP Provida and Banco de Chile. He has also been executive vice president for Chile and Latin America of the New Zealander Carter Holt Harvey, not to mention his time, since 2000, in the multinational International Paper, the largest forestry company in the world based in the US city of Memphis, Tennessee, of which he even became its first vice president, as well as president for Europe, Middle East, Africa and Russia.

“I don’t think anyone in Chile has come this far in a transnational company of that magnitude,” says Tironi, who is emphatic in assuring that “he is a man of the left, clearly, so it is very unfair that someone in this past attributed to him intentions to privatize Codelco and those absurd things.” In this regard, from the dissidence of the Socialist Party, a collectivity of which he is a militant, they are categorical in clarifying that “Máximo (Pacheco) is a socialist with a concertacionista heart, but who, unlike his fellow generation, has been able to read the national political moment, especially after October 18, making a reflection of the good, the bad and the perfectible of what those governments were and what this new socialism implies.”

Likewise, from the dissidence – which is to the left of the hegemonic currents within the formation – they affirm that their commitment to changes is such that perfectly “it is located to the left even of the senators of the PS”, who have been harshly criticized for subordinating the desires of the Chilean people to their corporate interests, since – in the opinion of this sector – they have renounced to support with enthusiasm the option of the Approve and President Boric himself. “In fact, (Pacheco) has proven to be one of the most committed bacheletista socialists,” adds a source consulted.

Sierra Parra delivers an opinion that, in his opinion, reveals part of his sensitivity to the world of work: “I can attest, in the period that I had to work with him in the 90s, that Máximo Pacheco demonstrated a great sense of social responsibility and respect for union organizations,” emphasizes the former vice president of Human Resources of Codelco.

But not everyone was surprised by Pacheco’s ability to defuse this real bomb. “The man knows because he has a political wrist,” says the main leader of a citizen organization, who met Máximo Pacheco when he headed the Ministry of Energy. “We work together on a specific matter that today is worth it,” he details, referring to another great mole that drags his ministerial management in Energy: the transitory article that allowed Metrogas to create a mirror company (Agesa), in order to artificially bulk up the charges to its customers.

“He no longer runs private companies, but he has never stopped being a man of that world. I don’t know if it’s possible to stop being part of that world,” responds the source who was part of Ricardo Lagos’ failed presidential campaign. “It is not one of those that will affect the interests of companies. I think that happened with Metrogas. It is very aware of this legal certainty to attract investment, to maintain theeglas of the game and act or regulate forward, but never backward, because it assumes that any market failure is a lack of the State, of the country, not of the company that takes advantage of the opportunity that opens up to it, “he adds.

Nolberto Díaz also alludes to his controversial role as manager of the arrival of a giant: “He was the great promoter of the arrival of Gas Natural Fenosa in Chile, the same one that came to subcontract essential areas and then sell the business to the Chinese.” For Díaz, Máximo Pacheco is an ally of the country’s great fortunes and an enthusiastic defender of corporate interest, which explains “his support for AES Gener projects or what happened with Metrogas”, a situation that would provide clues to what for him and the ENAP workers seems a sensible certainty: “His arrival at Codelco tells us who continues to govern this country.”

Nolberto Díaz regrets that the least luminous part of the transitional culture is prolonged in a country that demands different practices and perspectives, such as due transparency and political responsibility in the face of errors and horrors committed in the exercise of public office. So far, his critics regret that Pacheco has not provided a detailed explanation of what happened in the Metrogas case. In fact, the senator for Antofagasta Esteban Velásquez, of the Social Green Regionalist Federation, said after learning the news that referred to this notorious scandal: “I wonder if the then Minister of Energy (Máximo Pacheco), who today is president of Codelco, in a few more years will not be giving explanations and excuses regarding his management in Codelco.”

But it is already known: his figure is always a source of discordant opinions. “We’ve had good dialogue for a long time. With Máximo Pacheco it is easy to reach agreements, because with him you can always talk. He is not that arrogant person that one unfortunately knows in these kinds of matters. And you can tell that he listens,” emphasizes, instead, the spokesman of the social organization that spoke with him about the need to reform the gas industry.

Another interesting biographical fact is that he lived in Russia between 1965 and 1968 thanks to his father being ambassador to the Soviet Union, an experience that only a handful of Chileans could know in the twentieth century.

The leader of the social organization consulted by El Mostrador adds: “Máximo Pacheco has the ability to connect well with the problems of ordinary people. Culture helps to approach social problems and phenomena in a very different way. We have seen how other entrepreneurs behave in everyday life or in stressful situations.” In this sense, the current president of Codelco would be aware that opportunities have never been lacking, according to those who know him: when he was very young he was an analyst at Banco Osorno, and then he served as manager of planning and studies of the ill-fated Banco de Talca, a place he arrived at thanks to the efforts of Sebastián Piñera Echenique.

Later he ventured into the Bank of Chile, from where he helped to raise three projects before the entity was intervened by the State: afp Santa María, Leasing Andino and Banchile Agencia de Valores.

This is another critical knot in his biography: his close link with the private world, which never ceases to arouse suspicions in those who doubt the bidirectional transit between private enterprise and the State. “What happens is that sometimes you get confused by your business side, and in that sense he has never set a position of rupture with that area,” adds Daniel Sierra Parra, something that some question, since – they remember – Pacheco decided to move away from private enterprise after his time at International Paper.

Pamela Poo, director of Public Policies and Advocacy at Ecosur Foundation, was another of the voices that in her minute questioned the arrival of Pacheco to the copper company: “They appointed the former Minister of Energy, Máximo Pacheco, at the head of Codelco. He is a very suitable person, but with this choice it is clear to me that we will continue with extractivism and we will probably not have a glacier law.”

Politics in the blood

The same source who worked with him in the short-lived Lagos campaign highlights another element that has been little talked about here, and that also helps to get an idea of Pacheco’s political formation: “We must remember that he is a Matte. It is Máximo Pacheco Matte, let us not forget. He is a man of the elite, a person of the classic Chilean oligarchy, who was educated in one of the best schools in Chile and who frequents very restricted spaces for the common people. On the one hand, he relates well to companies and the elite because in those worlds, except for his political militancy, they do not see him as an outsider.”

By the way, Máximo Pacheco Matte is the son of the lawyer, academic, diplomátChristian Democrat politician Máximo Pacheco Gómez and Adriana Matte Alessandri. From his maternal family he has a link with two former presidents of Chile: Arturo Alessandri Palma and Jorge Alessandri Rodríguez, great-grandfather and great-uncle, respectively. It goes without mentioning all the politicians surnamed Matte who have starred in Chilean politics for more than a century.

“He’s used to this. His knowledge of the political world and this whole matter of negotiation is something of family, also because he himself has an intense life in that sense, since from a very young age he was part of the MAPU, “he adds, referring to his former militancy, when, being still very young, he celebrated the triumph of Salvador Allende while his family, terrified, she visualized a real assault on the Winter Palace on Chilean soil.

The source who worked with Pacheco when he assumed the role of Generalissimo of Ricardo Lagos agrees with that innate political nose, which makes him act decisively. “I think it was clear to me that the workers (of Codelco) did not have all the chances of winning because of the rejection generated by this attitude of closing themselves to the conversation, especially when they have been assured of their jobs and while people get sick from living in a sacrifice zone. He looks selfish.”

At this point, as in the mountains, Pacheco took risks, which ultimately turned out well, but if he had fallen he would have dragged the entire government in his path.

Follow us on