That night, Mark didn’t throw a brick or face a cop. But he did carry with him something that could be as powerful as any other projectile: a chalk.

His friend Marty gave it to him as chaos unfolded outside the Stonewall Inn bar, where police were bombarded with coins and bottles.

The teenager took to the streets to scribble three words on the pavement. Then he did it again on a wall on the same street.

That simple message written by Mark was an attempt by Marty Robinson to spread his message, to make sure that a spontaneous act of resistance was going to turn into something bigger.

An hour earlier, police had raided that bar in new York’s Greenwich Village, the second time that week, but now it was a Friday night at 1am, when it was crowded.

About 200 customers – lesbians, gay men, transgender people, escaped teens and drag queens – were sent out on the streets. A crowd turned against the agents who took refuge inside for safety. Homosexuals were used to fleeing the police, but this time they were the ones on the offensive and the police men were on the offensive.

The gay rights movement did not begin that night, but it was revitalized with what happened in the hours and days after the first coin was released.

And all the steps taken since then, such as equal marriage and a more receptive society, owe something to the young people who faced the police and the activists who organized theway afterwards.

Stonewall has been compared to the stock of Rosa Parks. Parks’ refusal to give up his seat on a bus in Alabama to a white man had the effect of bringing the civil rights movement to life 14 years earlier. Similarly, Stonewall pushed the fight for equality in the gay community.

In the United States of 1960s, gays and lesbians were practically outlawed, living in secret and in fear. They were labeled crazy by doctors, immoral by religious leaders, of government incontrarate, of predators by news and of criminals by the police.

So what suddenly pushed them into the fight on the night of June 27-28, 1969?

A fury with years of gestation

At the time of the uprising, consensual sex between men or women was illegal in all U.S. states except Illinois.

Gay people could not work for the federal government or the military, and if they came out of the closet they were denied the license to practice many professions, such as law or medicine.

The laws in New York State were particularly punitive, despite – or perhaps, in part, in response to – that a growing number of gay men and women across the country were moving to New York City.

Thousands of people were arrested each year in that city for “crimes against nature,” prostitution or lasctive behavior.

Some ended up with their names published in the newspapers, which meant losing their jobs.

There was a lot of anger because the gay community had no political power to prevent this, says William Eskridge, a professor at Yale Law School. “It was like a powder room waiting to be set on.”

Young gay people did not want to write letters to their rulers to enact or sign petitions, he explains.

Instead, they followed the example of the anti-war, black power (black power) and those who fought for the liberation of women. His strategy was simple: “Go to the streets and create problems. Attack, attack, attack.”

There was no refuge for them in bars or nightclubs. Local alcoholic beverage laws in New York City were interpreted in such a way that serving alcohol to gays and lesbians could lead to the closure of any licensed premises, as it made it a “place of public disorder.” Dancing with someone of the same sex could be interpreted as a “lewd” offense.

In the early 1960s a crackdown began on the city’s gay bars.

The Mafia began to manage many of them, but despite this, Stonewall Inn’s clients considered it a sanctuary, a rare place to express themselves and show affection. Exceptionally, he had a dance floor.

As raids became more frequent during the summer of 1969, with a mayoral election nearby, the Stonewall Inn became an obvious target.

He was run by criminals and sold alcohol without a license. There were also rumors that the Mafia was blackmailing its wealthy clients. But the police had no idea what he was getting into: the sense of injustice could be felt, not only by recent raids, but also by several attacks carried out by vigilantes.

That night, the hottest of the summer, all I needed was a spark.

“We were counterattacking”

About six officers, including those leading the public morals division of the NYPD, crossed Christopher Street and entered the bar, where there were already undercover colleagues.

The lights went on, the music stopped and the police ordered people to show their identity documents as they came out.

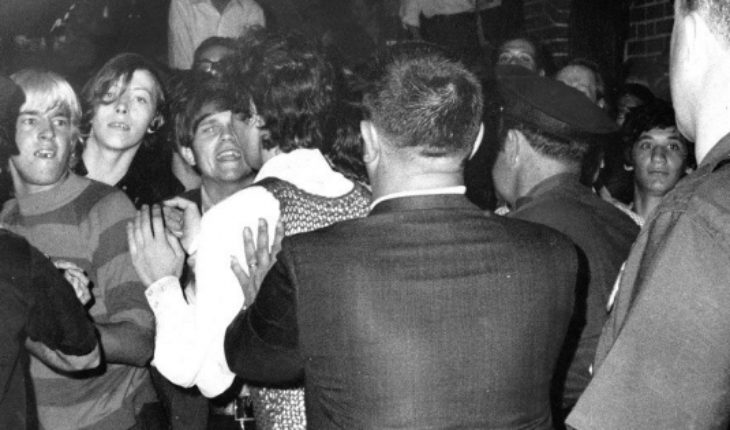

The ejected customers took to the streets. At first, the atmosphere was festive, says Robert Bryan, who was 23 at the time. He arrived at the scene shortly after the raid. “There were laughter and jokes. People came out of the bar doing poses and obeisances.”

She says the mood changed when a drag queen was attacked by one of the agents after she hit her with the bag. People started throwing coins at the police. The situation worsened when a lesbian came out of the bar and wrestled with the agents, who were trying to get her into a car.

That’s when “the missiles” ceased to be pennies and became stones and bottles.

When police took refuge inside the bar, he began grabbing and beating people, says Bryan, who kicked an officer before fleeing while someone else chased him in vain. When she returned, the police were trapped inside the property and, as they later revealed themselves, fearing for their lives. They were barely a handful while, outside, the protesters already added up to hundreds.

There was a riot.

“It was just an emotional moment, goothery of adrenaline, completely irrational,” Bryan explains.

There was a crowded spirit, it counts, and it felt like a dream state, of unrestricted acting. “God knows I would never have kicked a cop if I’d been alone. We were finally counterattacking and it was exciting.”

Riot police arrived to rescue their comrades, but the violence continued. At least one officer was treated in the hospital for a head wound and 13 protesters were arrested.

That battle was over, but some of those present knew that nothing would ever be the same again.

The next night, the crowd was larger, perhaps in part thanks to Mark Robinson’s chalk, but also to the distribution of flyers during the day. It was also more violent and the police took a more powerful approach and used tear gas.

The dumpsters were set on fire and thrown at the agents. The protests continued another four nights, Wednesday’s was particularly violent.

But the question that was in many minds when the uprising ended was: then what?

First steps towards freedom

When Martha Shelley, 25, climbed into a water fountain in a park near Stonewall exactly a month after the riots, she feared for her life. But he had an important message to say to the few hundred people who were there: come out of the shadows and “walk in the sun.”

“It was terrifying,” he recalls now, at 75. “I was in Harlem when MLK (Martin Luther King) was shot, and that burned fire. I was aware that I could get shot.”

At her behest and after a hectic speech by Marty Robinson, they had all marched to Stonewall Inn, some with lavender bands, holding hands and singing “Gay Power!” (“Gay Power!”). Once there, Shelley told the crowd to disperse as she feared more violence would occur.

That was the first time gays marched openly in New York, demanding equality. In Philadelphia, for a few years there was an annual picket in front of the Independece Hall, led by the Mattachine Society, the first major gay rights organization. But that was a polite thing, according to Shelley.

“I went to Philadelphia. Women had to wear dresses. I hated him with all my heart. We walked with our signs and tourists looked at us as if we had escaped from a zoo while eating their ice cream. I thought, ‘This isn’t me, it’s a farce.'”

Before Stonewall, activists wanted to fit into society and not shake the boat. But after the uprising, polite demands for change became outraged demands.

Organizing

This new mood was best shaped in what became the most important driving force that emerged from Stonewall: the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). It was formed in a matter of weeks and was both a flexible alliance of groups and a single entity.

The name was a nod to the National Liberation Front fighting the United States in Vietnam. When they suggested it at a meeting, Shelley became so excited that she hurt her hand with her beer bottle and ended up bleeding. “The riots wouldn’t have done anything if we hadn’t organized later,” he says.

The GLF only lasted a few years, but shone during that time, with a range of problems to fight against.

“It was paramount to have control over your own body,” Shelley recalls.

The GLF made alliances with some of the major insurgent groups of the time, such as the Black Panthers. Its members organized the first Gay Pride march and created a newspaper called Come Out! that Shelley sold on the street.

The GLF meetings were chaotic and there were major disagreements about how best to move forward. But its creation ushered in a new era that spawned a wave of new groups such as the Gay Activistalliance (GAA) and the radical lesbian group Lavender Menace (Lavender Threat), of which Shelley was the founder.

A year later there was a GLF in London and the movement went global.

The First Gay Pride Parade

Today, there are thousands of Gay Pride events around the world. But his beginnings were humble: the idea of a more radical march to demand rights came during a dinner of three friends shortly after Stonewall, says Ellen Broidy.

Liberation Day on Christopher Street, exactly one year after Stonewall, began in Greenwich Village and toured 51 blocks down Sixth Avenue to Central Park. Between 3,000 and 15,000 people reportedly participated.

The most exciting was the number of people who joined along the route, Broidy says. “The central message was ‘We’re here. We’re weird, get used to it.’ But I felt it was more than that, it was about getting there and playing our part in the revolution.”

“I don’t think any of us were marching for the right to join the army or get married.” According to her, the annulment of systems of oppression was sought more than a legal change.

Some women were so sure there would be violence, they took self-defense classes. But there wasn’t. Other U.S. cities soon joined and, two years later, London had its first Gay Pride event.

“It was natural and necessary,” Broidy says. “If it hadn’t happened first in New York in 1970, it would have happened in London or Madrid or Mexico City.”

Today, the political message is still there but Gay Pride is more of a celebration of gay culture with music and business sponsors.

Broidy thinks something’s been lost along the way.

“I think it would be much more powerful without the floats and without Citibank or American Airlines. Yes, it is a sign of progress, but in an unmistakably capitalist market.”

Steps forward

After that first March of Gay Pride, progress accelerated.

In the following decade, federal bans affecting gays and lesbians were eliminated, and the medical profession reversed its belief that homosexuals needed psychiatric treatment.

In 1977, Harvey Milk became San Francisco one of the first openly elected public office in the United States. Two years later, about 100,000 people took part in a national march in Washington. Probably, at that time, this was the largest congregation of homosexuals in history.

Many of the laws against sodomy were eliminated in the 1980s, which made homosexuality effectively legal, although decades passed for gay marriage to become a federally recognized right in 2015.

Legal progress was accompanied by a shift in attitudes: today, three out of four Americans accept homosexual relations.

In 2019 and in the United States, there are still battles to fight: gays can be fired from their jobs in many states. Activists say Donald Trump’s administration is pushing the country back by withdrawing some of the freedoms that were fought so hard.

But the appearance of the first openly gay presidential candidate (Democrat Pete Buttigieg) suggests that, in general, the North has not been lost. Perhaps the greatest sign of progress is that the aspects of Buttigieg that cause more curiosity are his unusual surname and his ability to speak Norwegian, not his sexuality.

None of those who fought the police that night or marched in the streets could have predicted the progress that was made thereafter. So it’s worth reflecting on everything that came out of that mob raid on a mafia bar, says David Carter, author of “Stonewall: The Riots That Unleashed the Gay Revolution,” a book considered the definitive account of what happened.

“It is very unexpected and very unusual in human history that something that is a totally spontaneous act has changed for the better the course of human history.”

This was not the first gay confrontation against the police. As the newspaper recently recalled Los Angeles Times, the police had been bombed with doughnuts 10 years earlier. But it was the most important.

“It went from being microscopic in size to a massive movement, that’s the historical significance of Stonewall,” Carter says. But it also has a deeper meaning, he says. “Moments like this take on inspiring meaning, so in terms of American history, it compares to when MLK delivered its ‘I Have a Dream’ speech at the Lincoln Memorial. Or when the sailors raised the flag over Iwo Jima.”

But unlike the other famous stories, Stonewall’s is not taught in many schools. However, it is remembered in other ways: in films, books and even in heritage. In 2016, the area around Stonewall was designated a national monument and in early June, the New York Police Department apologized for the raid.

What Mark did next

So what happened to Mark Segal, the teenager to whom his friend Marty gave him the chalk?

When the raid was made at Stonewall Inn, he had only been in New York for six weeks and was staying at the YMCA hostel for $6 a night. The resistance was nothing new to him, his first act of rebellion was when as a Jewish child refused to sing OnwardChristian Soldiers (“Forward Christian Soldiers”) at his school in Philadelphia.

Outside Stonewall that night, he thought, “We are fighting for our rights, just as women, African-Americans, and others did throughout history.”

That night, the police were a symbol, he says. “It was the synagogue, the family I couldn’t tell the reason Why I had to leave the city I loved and move to New York. It represented religion, the media, the government. All the people who pushed us.”

But Stonewall was not just a fight, it was a spirit and gave Segal a purpose, he admits: he vowed to devote the rest of his life to a new vocation.

This took him first to the GLF, where he helped direct his advancement among the youth. He also took on another mission: to make gays as visible as possible to the American public. He did it through a strategy of public disorder. Or, as they were known, “zaps”.

In 1973, he broke into the prime-time newscast of the CBS channel hosted by television legend Walter Cronkite, where he was watched by 60 million people holding a sign that read: “Gays protest against the prejudices of CBS.”

Then he created a gay newspaper in Philadelphia. His work in the field of equality earned him an audience with President Barack Obama.

Before he got that piece of chalk 50 years ago, when he was a teenager with no penny on him, I could never have imagined the path he would follow.

“I would never have said that one day I would be dancing with my husband in the White House. So what I would say to someone who is young and thinking about coming out of the closet would be ‘Dream Big’.”.