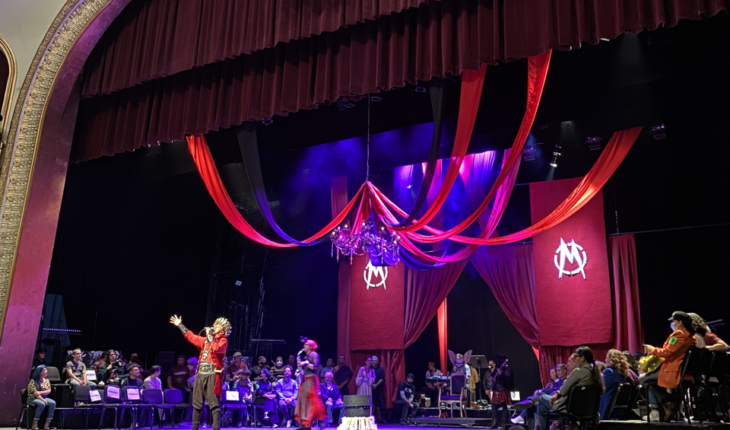

“Not one more,” chanted inmates of the Santa Martha Acatitla prison as the last line of the work MCBTH Pray for us, which they staged at the Teatro de la Ciudad, during the 90 minutes that were released to commemorate the 13 years of the Penitentiary Theater Company.

Outside, demonstrations for 25N, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, had begun hours earlier. On stage, Lady Macbeth, the central female character for the adaptation, insisted between anger and tears: “Women are marching. So far it was heard and we did nothing. Or do we not care?” Then, the names of some victims gave way to a “femirap” that closed with the slogan “Not one more”.

In an interview, Itari Marta, founder of the Penitentiary Theater Company, says that she really likes working with Shakespeare’s works because of their prodigious dramatic structures, but also because of the possibility of using creativity and her own vision of her texts. In this case, it was an adaptation focused on the gender perspective through the character of Lady Macbeth, considered the woman who became a murderer.

“I’m very interested in that figure because why does Lady Macbeth become an assassin? In a country like the one we live in, I have often questioned whether, to balance the balance, women do not have to become murderers to take care of ourselves,” she says. As part of that search and reflection on gender violence, I wanted to mount a play with the inmates of Santa Martha that spoke about it.

The actress and theater director stresses that among the fellow actors are those who committed the crime of rape, so it was crucial for her to question them about their perspective towards women and if they were aware of the involvement of their actions. Therefore, the play is developed around Lady Macbeth and not Macbeth himself. All members of the company contributed to the adaptation.

Similarly, Itari was interested in highlighting the characters of witches. “In this whole feminist movement, I have heard many times that they call us witches, I myself have been told; I really liked being able to talk about the witches and the female images of that work and how the men around them behave,” she explains.

Inmates of the capital’s prison system have had very few opportunities to go out and present plays or exhibitions. As on other occasions, just over 10 inmates arrived at the City Theater in the midst of a strong security device, guarded by uniformed and non-uniformed elements of the Secretariat of Citizen Security.

On stage, they met with the external Penitentiary Theater Company —made up of those who have already obtained their release—, with almost 50 people who have built the project for 13 years, as well as with their relatives and their former companions who are now free to occupy a seat and return to the streets, and not to the prison. when the curtain falls.

“The truth is that it took us many years to achieve that complicity with the institution, and we still have several people who do not measure the importance of culture and art for the human mind, but in any case, the Undersecretariat of the Penitentiary System puts at the service of the project a significant number of guards and people who make it possible for these comrades to leave … There are many people around, almost 100 people, who make it possible for those 12 or 13 people to stand on stage,” says Itari.

13 years of Penitentiary Theatre

It all started with a call 13 years ago. Itari answered the phone from the outside line of the Shakespeare Forum around 10:00 p.m. A voice asked if he would accept a call from a prison in the capital. On the other side of the line, Sara Aldrete was waiting, from the Santa Martha Acatitla penitentiary. Known for her book They call me the narco-satanic, is now serving a sentence of more than 600 years in the Tepepan prison.

Itari no longer remembers very well why he pressed the key to accept the call, but “that’s life: sometimes a decision that seems very small can lead you to very big things.” Sara Aldrete already had a theater company in Santa Martha Acatitla. Together with his partner Bruno Bichir, Itari had a program on Canal 40 where they interviewed independent theater companies.

Sara used to watch the show and wanted to be interviewed about the company she had formed in prison. “That was precisely the call with which we went to Santa Martha on the first visit. AfterIt is from that call, what happened is that the company that Sara had the forum helped her to produce the work they were doing at that time, which was Cats, the musical,” says Itari.

They managed to give a performance of that play open to the public, but, during the event, Sara talked about her particular sentence, which involved people within politics and entertainment. Itari believes that, with the intention of “taking away the megaphone”, he was henceforth banned from entering the Shakespeare Forum to continue the project with Sara. However, that caused the men in Santa Martha to watch the project and the TV show and call Itari to meet his own prison theater company.

“When I arrive, I realize that there are the perpetrators. Many years ago I suffered an express kidnapping, and the truth is that I did have a thorn in my heart regarding that issue; I never managed to understand well what had happened to me, and although one tries to live his life and get ahead, when you go through those situations, you never quite understand very well why you, why in your country, why the situation … You don’t quite understand what happened to you in a deep way no matter how many therapies you take,” he says.

Lee: What are we talking about when we talk about social reintegration?

When he met the inmates of Santa Martha, he understood that he had to face the figure of the perpetrators. Most projects, he says, focus on victims and rarely stop to work with the counterpart. For her, that is a much more forceful strategy, because no one cares about what happens to those who exercise violence when they are released. 70%, he recalls, return to prison.

From Itari’s perspective, it is important to reflect that prison does not end crimes, nor does it work in depth to make people understand the real damage they inflict on a society. In the project, he clarifies, there are many layers of information, but it is related in a primordial way to the importance of facing and working with these figures, understanding their circumstances and what happens to them through a different approach to the punitive society in which we live.

Reconciliation and professionalization

From the outset, prison theater affects the self-knowledge and self-questioning of people in prison, says Itari. It helps to make an analysis of what is happening to them internally. That exercise is one that in general human beings do not do, but theater forces a work of conscience in a playful and kinder way than other strategies.

That’s the beginning. After awareness, comes empathy, feeling again. On a next level, the theater allows us to imagine other possible scenarios. “What happens a lot with people who are involved in organized crime is that they don’t see the possibility of another world, and neither do the victims, and neither do those around us. We married ‘How bad everything is and this is the only thing that exists,'” says Itari.

These phases, like art in general, allow us to humanize and reflect ourselves in concrete moments and events. Shakespeare said that theater is a chronicle and a reflection of the present, recalls Itari. “When do we have the opportunity to see ourselves reflected in a mirror as humanity, and to be reminded that we are human, that we are people, and that those people feel?” he asks.

The third aspect that stands out is that, as a society, it is necessary to offer people in prison job opportunities and a better quality of life, not through gifts, but scenarios where there is the opportunity to live in an honest way and with an economic remuneration. Therefore, the external company gives usual or special functions, such as the City Theater, to collect the ticket, distribute what is earned among its members and make them feel remunerated for their work.

For her, it is essential to place this at the level of professionals, because theater in prisons is often seen as entertainment or exercise to “kill time”, and not necessarily as a trade or job. That is what distinguishes the project, according to Itari: that they have built a mechanism to give it a professional dimension, not only of training, but of a result for a paying public.

“For us, it’s also a job option. We still cannot get this to compete with organized crime, because art in this country is very precarious. In that same mirror, the theater allows us to make a society see that our artists are precarious, that we have the fourth most important billboard in the world but we are undervalued, and although many of us live from theater, it is a great effort to live from art. In that sense, also It is a criticism of the society that is outside,” he concludes.

What we do at Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Político, receive benefits and support free journalism#YoSoyAnimal