The one-year sentence of freelance journalist Roberto Quiñones is the first in the Cuban government of President Miguel Díaz-Canel and points to the turning point of what analysts and press freedom organizations consider a wave repressive to the non-state press, which dates back to the beginning of this year.

With the punishment imposed, the authorities went beyond the usual harassment of recent years, which summed up arbitrary arrests for a few hours and even days, intimidation, and confiscation of equipment.

You may be interested: Independent Cuban media denounce repression and aggression scrimels of Diaz-Canel government

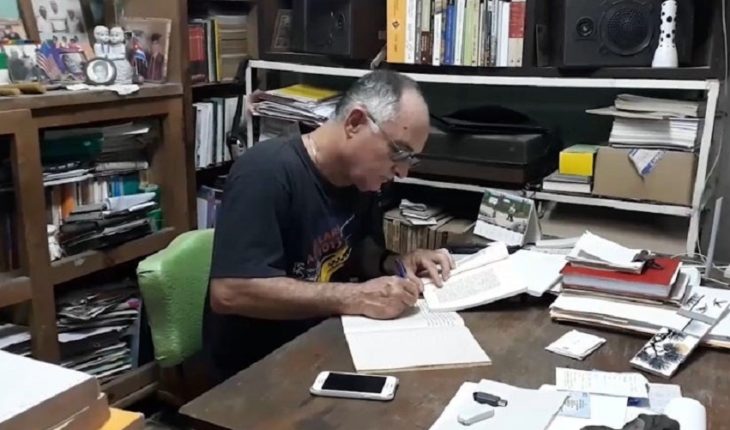

Quiñones, a 62-year-old lawyer and journalist who works as a correspondent for the Cubanet digital media, was arrested last April while trying to interview the daughter of a couple who was convicted of trying to educate her outside the Cuban education system.

In August, the Guantanamo municipal court, at the eastern end of the island, dismissed an appeal filed by Quiñones and ratified the one-year prison and community work sentence, after accusing him of “resistance and disobedience” to the authority when he was Arrested.

Arrests, harassment and forupings are carried out by police and security officers in the Cuban state, and most occur when journalists are reporting stories, such as Quiñones’ case.

Hugo Landa, director of the Cubanet digital site, for which Quiñones reported when he was arrested, says that the severity of the measure is due to various factors.

“First ly, Roberto has had a tradition of fighting dictatorship since the 1990s,” Landa said, flaking the condemnation in the context of Cuba’s energy crisis and the possible rationing, in the future, of other goods and services. “The government feels weak, fearful and wants to give a dig. He uses Roberto’s life to scare those who publicly disagree or do independent journalism.”

The direct link between the economic crisis in the Cuban archipelago and the increase in repressive measures is also observed by Henry Constantín, vice-president of the Inter-American Press Society for Cuba.

Read more: Twitter blocks the accounts of Cuba’s main official media as well as Raúl Castro

The stores and markets in Cuba have suffered from product shortages in recent months because of the lack of money to buy them in the international market. At the end of September, car fuel began to run low due to transportation problems from Venezuela, the main supplier of gasoline to the island.

The scarcity has revived the ghosts of the special period, a long economic crisis caused by the fall of the Soviet regime in the 1990s, which was then the main purchaser of Cuban products such as sugar and gasoline supplier.

The special period resulted in a deterioration in the quality of life of the population and, in economic terms, a sharp contraction in the economy that were faced with severe restrictions on the consumption of commodities and fuel. This caused unrest in the population and the exodus of thousands of Cubans to the United States and Europe.

Quiñones’ case alarmed international organizations over the circumstances of his arrest, trial and conviction and was included on the OneFreePress list of the 10 most pressing cases of injustice against journalists.

Amnesty International appointed him as a “prisoner of conscience.”

“Quiñones was arrested and beaten while covering a trial, and this injustice represents an even lower level, even for a country with a long tradition of censorship like Cuba,” said Natalie Southwick, coordinator of the Central and South America Program Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Outside of the conviction of Quiñones, the Association pro Libertad de Prensa (APLP) of Cuba has reported 76 more assaults on independent journalists from January to July this year.

20 of these assaults were directed against women. Most of them were prevented from leaving the country to attend professional training or events that had human rights conferences on their agenda.

On 25 June last, for example, the Cuban authorities prevented journalists Ileana Colas and Maricel Naples from leaving the country who were to participate in the General Assembly of the Organization of American States.

The reporters, who were traveling with other activists, were invited to expose the situation of the independent press and freedom of expression in Cuba.

When they arrived at Havana airport, immigration officials informed them that they could not leave the country. Currently, 60% of journalists who have exit bans are women, according to data collected by APLP.

The trial against Quiñones began three months earlier when, at the entrance to the same court that sentenced him, the journalist was preparing to interview Ruth Rigal, the 13-year-old daughter of evangelical pastors Ramón Rigal and Ayda Expósito.

The couple were accused of committing “acts contrary to the normal development of the child” by wanting to educate her at home and was sentenced to one year in house prison. In Cuba, by constitutional mandate, education is secular and state-owned.

Within minutes of the interview with Rigal, two state police officers approached Quiñones and interrupted the conversation. They asked him for id and notified him he was in custody.

The reporter says he asked the cops about the reason for the arrest and that the answer was to apply a physical defense technique to subdue him.

“He spun me around, and pulled me with such violence that I fell on the sidewalk from the small courthouse ladder,” Quiñones told the Institute for War & Peace Reporting (IWPR).

On the way to the police delegation, the journalist says he was beaten by the authorities, causing injuries to his face, hands, neck and ear, which were certified by two independent medical institutions.

“Inside the patrol car I told him I was an abuser and he beat me savagely,” Quiñones said in reference to the policeman who arrested him. “They broke my lip and the tip of my tongue, just as they hurt my left thumb and slapped me on the right side of my face, above my ear.”

Authorities said the violence against Quiñones was “necessary to reduce it to obedience,” according to the court documents on the criminal record against him.

After his arrest, he was confined to a dungeon for five days with his body full of bruises and bruises, a bloody shirt and a perforated right eardrum, according to a medical certificate.

The day after his arrest, he was transferred to a hospital where, he said, he was examined by several doctors who certified the injuries but received no medical treatment.

A day later, the reporter was taken to the Cuban government’s Department of Legal Medicine, where authorities told him that the injuries did not pose a life-threatening risk but that if they required medical treatment, the journalist says.

The policemen who beat him were cleared of responsibility by the First Military Prosecutor at Guantanamo on April 30. En la sentencia que condena a Quiñones a prisión, se afirma que los funcionarios cumplían con su deber.

Guantanamo police authorities have a number of known history of violence against arrested persons and inmates. On October 19, 2014, Cuban Antonio Leyva Tejeda, 39, died in the provincial hospital, the victim of a beating received in the same police unit where Roberto was transferred, as reported by the Cubanet digital media outlet.

In the same year, human rights activist Ulysses Garcia reported another beating by the provincial police, which caused fractures and injuries.

Find out: Cuba, America’s only country with no guarantees for the exercise of freedom of expression

The press freedom organization Article 19, which has been watching the new repressive wave of the independent press in Cuba and in particular the conviction of Quiñones, relates the magnitude of the punishment to the control of information in Cuba.

“With independent press, control of the information flow goes hand in hand with the Cuban government and so the severity of the measures has increased,” said Claudia Ordóñez, the organization’s director. ” (Quiñones) could be an exemplary punishment for his colleagues.”

The journalist was due to enter prison on September 12, but Cuban authorities advanced his incarceration date for the 5th and police arrested him at his home. Six days later he was taken to Guantanamo provincial prison because Quiñones refused to serve his community work sentence.

“During the prosecution, the journalist was raped time and again by his legal guarantees,” says lawyer Laritza Diversent de Cubalex, a non-profit association that defends and promotes human rights in Cuba. “Roberto Quiñones did not have access to an independent court or impartial judges as no one in Cuba where the judicial system is contingent on the government.”

The journalist was not allowed to defend himself as he had requested, nor was he given time and resources to do so, he said. He added that he went to the trial without an advocate, who never had access to his file, nor was he admitted the evidence he wished to present.

Evidence is photographs of the injuries sustained and a history of harassment written by Quiñones himself, recounting the persecution he has suffered by the security of the state of his province for years.

Last February, state security had prevented the journalist from traveling to Havana. Then, on April 18, he was forced off a bus heading to Cienfuegos, where he went to visit his elderly and sick parents, he said.

Both acts were executed by the Cuban political police officer known as Victor Victor, the same one Quiñones accuses of ordering the cops to arrest him the day he worked as a reporter in court.

In Cuba, members of state security do not use their real names but pseudonyms to prevent their identity from being exposed.

By hiding their names, it is more complex to place them as agents or to prevent their entry to third countries because of the repressive activities they have committed on the island.

Since 1994, Quiñones has suffered political persecution in Cuba for defending political and human rights activists as a lawyer.

Two decades ago, he was held in prison for more than four years, accused of falsifying public documents and receiving bribes. The journalist says he was charged with complicity with a notary that he was defending.

The notary had been processed for authorizing the sale of a house, which was forbidden at the time. These transactions were authorized in 2011.

Quiñones says he did not work in the office where the law was inflicted and had no access to any documents. He also said he was convicted of not continuing to defend activists.

“The Cuban government usually sanctions as common criminals and accuses people who belong or relate to the opposition or the independent press of non-political crimes,” Quiñones said. “He did it with me more than 20 years ago, and he did it again today.”

Claudia Padrón Cueto is a Cuban journalist who collaborates with Tremenda Nota.

This story was originally published in English on the Institute for War and Peace Reporting website.

What we do in Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Politician, receive benefits and support free journalism.#YoSoyAnimal

translated from Spanish: Roberto Quiñones, the Cuban journalist who has been in jail for 78 days

November 30, 2019 |