Is it necessary to revive authority? Yes, because it is a basic mechanism for the peaceful, legitimate, stable and democratic administration of power in any human group. It orders our coexistence as people, in a family, a school community, a country, etc. We attribute or recognize that authority to another, so that he decides certain things, organizes us, sets rules, commands us, etc. We obey that authority by consent, voluntarily, by its legitimacy, its merit, and its ability to persuade us. He must not resort to force to make himself obeyed, but only by exception. It is important that whoever exercises authority has moral, intellectual, political prestige, or great technical or other capacity, because that is how we respect and obey him more. And if he does not exercise his authority, he will lose it, democracy will weaken, dictatorships and authoritarianism will emerge.

The loss of authority is a phenomenon in many countries of the world, which began in the mid-twentieth century. It is not a terminal illness, because the world and Chile have had periods of anarchy or lack of authority in history and have overcome themselves.

And how do we revive the agonizing or resurrect the newly dead? It depends on the cause. But basically we reverse or replace that which failed or caused agony or death. For example, reanimating the heart with rhythmic pressures on the chest or with electric shocks and giving mouth-to-mouth breathing to restore oxygenation. And if it’s bleeding from a serious wound, we make a tourniquet to cut off the flow, close the wound and inject blood.

And what has caused the agony or death of authority? Let’s say two obvious causes. Its lack of exercise, because the legitimate authorities must have the courage to exercise it and ensure that it is respected, without coercion or violence, and they are not doing so. It’s been uphill, I know. But parents, teachers, policemen, rectors, ministers, President of the Republic, etc., cannot renounce it. If they do not exercise it and do not enforce it, they will lose it, it will vanish and the community will be affected. The second obvious cause is the lack of ethics, stature, prestige or intellectual merits in those who embody authority. The authorities must respect themselves and dignify themselves. And if such merits are not seen, they do not respect or obey them. Authority is also earned.

But let’s explore other probable and deeper causes of the agony or death of authority.

One is contemporary nihilism, which consists in not believing in anything, not in a value system, not in God, not in an authority. Thinking that life has no meaning. Nihilism is nothingness. Nietzsche glimpsed it in the second half of the nineteenth century and anticipated it by a century, announcing and thinking about nihilism and the “death of God”, something that began with the Enlightenment. For Nietzsche, Western culture had reached its ruin, its total decadence. It was empty, exhausted of the “fictitious values” represented in metaphysics, Christianity and the old morality. Metaphorically Nietzsche summed all this up by announcing that “God is dead” and that we kill him. This contemporary nihilism can also be associated with the crises we are witnessing of traditions, churches and religious beliefs, which were associated with moral and hierarchical systems that also sustained authority and that have been fading along with them.

What if “God is dead” (who is the supreme authority), and values have been exhausted and life has no meaning, what authority could be sustained and subsist? I think none. And what can we do then? Perhaps rethink ethics, reconstruct or create other value systems, generate new existential senses, recover spirituality, transcendence or faith. Nietzsche tried to do his own thing, developing the idea of the “superman” and remembering that of the “eternal return”. Because Nietzsche did not “kill God” to stay in nothingness, but so that something new would arise.

Another cause of loss of authority is the extreme individualism of today, which emerged with the Industrial Revolution and liberalism, exalted to the maximum in recent decades. Individualism resists the collective interest, loses the sense of the common good. Let each one scratch with his own nails and demand his own, his own good over that of others and the collective. That kills the community and weakens the authority that leads it, because it diminishes its meaning or justification. Today we have a great atomization in society, multiple claimsindividual and identitarian institutions, and little mediation of institutions that organize interests and common goods. So it is difficult to exercise authority. What could we do? Perhaps we should further restore the social fabric, foster more collaborative networks, solidarity systems, organizations that represent and mediate collective interests. If there are no intermediate mediations, society becomes more ungovernable by authority.

As a third cause, I see that, in the middle of the twentieth century, all the ethical emphasis chips were placed on human rights, which are basically individual rights and freedoms. It was done to prevent a repeat of barbarities such as those committed during the Second World War. It was and is necessary, right and justified, also their full respect. But it has not had a correlation with a system of essential duties that we all have with others, with the community and society. If we do not make explicit and incorporate into our culture essential duties, the citizen does not understand why he must obey an authority that demands something that in reality he should not or is not obliged, nor does he respect the other or what is common to us. What can we do? Develop a system of essential duties of the human person, which is balanced with individual rights and freedoms. Duties are also essential bases of our coexistence, they also point out what we value in society, generate links of people with the social pact, the country and fellow citizens.

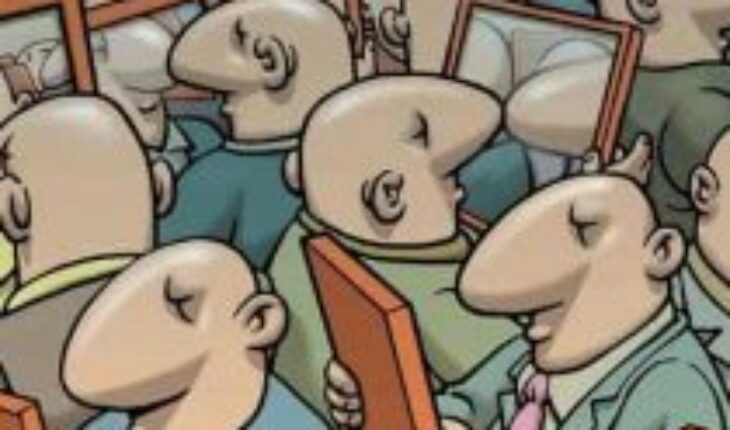

A fourth cause of the loss of authority is, in my view, the democratization of access to knowledge and information, and the development of horizontal communications technologies. Today almost everyone has access to TV, radio, internet, Google and social networks. This allows us to all access the same information and news instantly. Also to knowledge. And we can communicate with many others online, immediately and horizontally on the networks. Exclusivity in the possession of knowledge and information was formerly a source of power and authority. But such exclusivity no longer exists, which weakens authority and produces horizontality of power. Also in social networks nobody rules, we are all “equal”. That democratization and horizontality that make us equal are not bad in themselves, on the contrary, they are positive. The issue is how we face this new reality that is irreversible and has a negative impact on authority.

Perhaps, as Kathya Araujo has proposed, we should rethink authority and develop new systems to administer power in a peaceful, legitimate and democratic way, I think perhaps more participatory and horizontal, instead of as representative as they are until today.

Follow us on

The content expressed in this opinion column is the sole responsibility of its author, and does not necessarily reflect the editorial line or position of El Mostrador.