In a previous chronicle about the poetry of Paulo Maluk we stated that in the lapels of his books there was no indication about his person, except for the place and date of his birth: Santiago de Chile, 1973.

In this new collection of poems something similar happens, because there are no biobibliographical data. We are almost before an enigmatic poet like those philosophical, historical and literary Borgean characters who only had existence in their imagination.

However, the paratext that precedes the versal structure gives it real existential consistency. The writer of the prologues is Rafael Rubio Barrientos -his contemporary, by date of birth-, son of the poet Armando Rubio Huidobro. In this writing, the graceful form stands out, a condition that favors the elevation of the language of the poet Maluk. No doubt he is right. It seems that Maluk’s poetics go down this path.

Having read more than one of his books, we believe that Maluk’s poetics sits on the basis of lightness, not only in the scriptural form but in his deepest inner being. Lightness is not an undermining but, on the contrary, an essential quality of existence, in this case, poetic. It is like the unbearable lightness of the being of the Czech writer Milan Kundera. In the lightness of Maluk’s writing process is hidden the elevation of the word, as the poet Rubio says.

This phrase is very significant, because poiesis -in any of its lyrical manifestations- is the conditio sine qua non of the poetic act. The elevation of the word by the lightness of it is one of the greatness of poetry.

The poetic language unravels and decentralizes the everyday forms of the language and transforms them into a particular speech that, in the case of the poet Maluk, is in the lightness, the graceful, the tenuous, which has -although it seems contradictory- an existential weight in the versal structure. Lightness, in this sense, is connected to one of the oldest scriptural forms of prosapia in universal literature such as aphorisms or epigrams.

Both scriptural ways refer to a brief discursivity – lightness – whose content is judgmental, in other words, they always contain a truth; “So much thinking about death / I abandoned life.” Maluk’s poetry can be categorized in both categories.

Moreover, the lyrical speaker who unfolds in his poems is also witty, satirical and moralizing, even if he is parodic, almost Parrian: “I find living expensive / said the stingy.”

On the other hand, and taking into consideration the other collections of poems of his, one can glimpse in the poetics of Paulo Maluk a kind of religious background, in the etymological sense of the term.

It is an attempt to link what is separate. In this sense, a form of existential struggle emerges in the lyrical speaker between the believer and the unbeliever, between the one who sees the Light and the one who is blind to it. To be or not to be. In a way, in the lightness of Maluk’s poetics there is a tremendous existentialist question of a speaking subject who struggles in combat: “Do we deserve death? / We deserve life.”

“When I am foolish/ I pray to God heal me / Recover my judgment / I am filled with grace.” This poem begins segment VI of Maluk’s work, which is structured on the basis of the number VII, the number that indicates perfection from the numerical symbolism of the Judeo-Christian tradition, without this meaning having an esoteric meaning.

Medieval exegetes knew how to discern the senses of symbolic numbering well. Seven is perfection, unlike the number of the Beast. That is why the lyrical speaker in his existential struggle – which at times, is almost an agony – does not hesitate to invoke faith – one of the three theological virtues – even if it is incipient or shallow: “Good faith / the pious”.

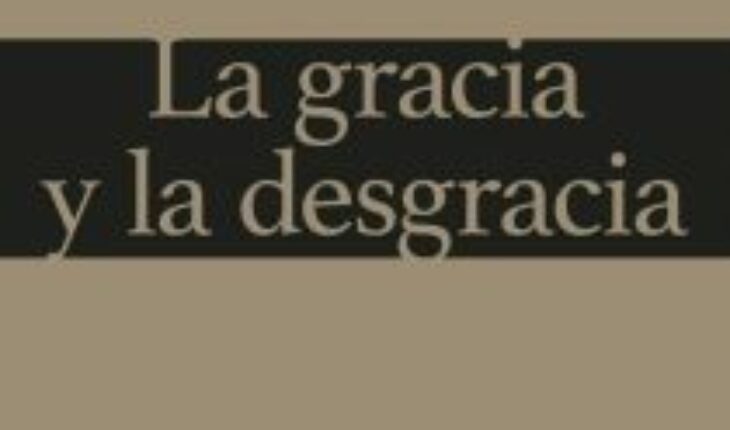

The poem with which we open this paragraph highlights the meaning of the title of Maluk’s poetic work. It is a denomination that we read on the basis of religation. The cover is almost aseptic. It is clean of any ad hoc diagramming. In the center stands the title with letters increased in the size of the font. There stands out the word grace, in the first place.

This is the core of the sentence, because the term after the copulative conjunction comes to mean the adjunct, what is intended to disdain. The word grace has a religious meaning that points to God’s free gift in order to sanctify our soul. It is called sanctifying grace. The lyrical speaker holds that “If I did not believe in grace/ I would be more miserable.”

Misfortune, the word, has more than one meaning, among them, knowing oneself in a situation that produces pain and suffering. Undoubtedly, we are facing a poetry that is not strictly religious. It is an apprehension of the world and of existence that starts from a speaker who struggles in the struggle – the title of the book of poems expresses it: “Each letter is my prayer.”

Surprisingly, in between the epigrammatic or aphoristic poems, an exceptional sonnet appears that, in a way, answers the existential questions of the speaker/author/reader. Here is the first quartet: “Sonnet of life succor the wretch/ Who fears death for fear of life/ Alexandrian encourage him and hurry up later/ And die at his death and not die to his life.”

In short, Paulo Maluk’s work will not disappoint the reader. It is a text that leads us to a poet in crescendo. The dedication to Armando Uribe Arce is also a paratext that cannot be ignored in the process of reading.

(Paulo Maluk: Grace and Misfortune. Santiago de Chile. Ediciones Quinta. 2022. 77 p.).

To learn more about what is happening in the world of science and culture, join our community Cultívate, El Mostrador’s Newsletter on these topics. Sign up for free HERE

Follow us on

The content expressed in this opinion column is the sole responsibility of its author, and does not necessarily reflect the editorial line or position of El Mostrador.