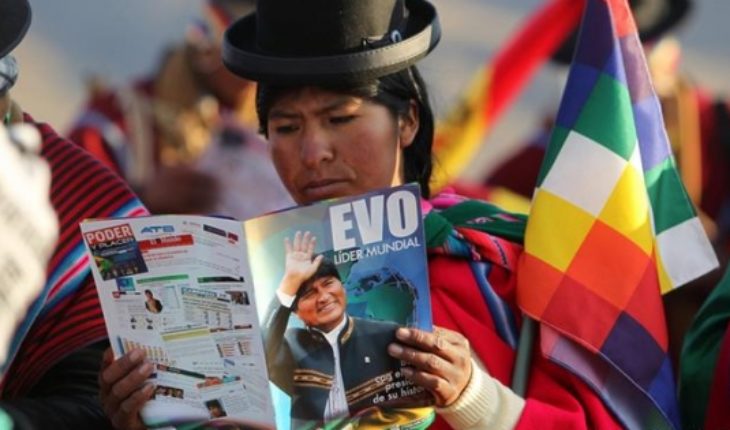

Some speak of the “Bolivian miracle”. Others call it “productive community social economic model” and some simply call it a “Bolivian state project.” The truth is that, by all indicators, the economic program implemented in Bolivia since the coming to power of Evo Morales in 2006 is the most successful and stable in the region.

Bolivia shows solid numbers: in these 13 years, GDP grew from $9 billion to more than $40 billion, GDP per capita tripled, real wages increased, reserves grew, inflation ceased to be a problem, and extreme poverty fell from nearly 38% to 15%. It’s a 23-point drop. In the same period, for example, extreme poverty in Uruguay fell by 2.3% and in Peru by 12%.

The keys

What happened? Everyone agrees that the change began with the nationalization of hydrocarbons in 2006.

“Our economic model works in a simple way: we use something that nature has given us. With neoliberalism that wealth was in the hands of multinationals. We nationalize to have a surplus that is distributed in two phases: reinvestment for the economic base and, on the other hand, the redistributive part of income”, says the Minister of Bolivian Finance, Luis Arce Catacora, in conversation with DW. He, together with the late Carlos Villegas, was the great architect of the “Bolivian miracle”. He adds, on the role of the state: “That redistributor role has allowed us to grow much more than any other country in the region.”

But getting here wasn’t easy. Morales took over in January of that year after a rebellion. In October 2003, the country had experienced what is known as “the gas war”, a popular uprising that erupted in the face of the decision of then-President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada to export gas to the United States via Chile.

From this insurrection emerged the “October agenda” that contained basically two demands: the nationalization of hydrocarbons and the drafting of a new Constitution. With that agenda, Morales assumed his first run.

But the country was still convulsed. “The new is not born and the old does not finish dying,” said Vice President Alvaro García Linera, who warned of the existence of a “catastrophic tie” between sectors, which paralyzed the country.

The dispute was open between state power in La Paz and the elites of the wealthy medialuna, the Bolivian east, back on the border with Brazil. There were shots of state institutions in those regions that were fighting for their autonomy and even a thwarted guerrilla attempt before kick-off.

Cornered, Morales called a revocation referendum in 2008 for all charges. He got more than 67 percent of the vote and summoned opponents to the table. From that moment on, the board was reordered. The symbol was the adoption of a new Constitution that refounded Bolivia. The first stage was over, which the government called the Democratic-Cultural Revolution. Then, in the 2009 presidential election, the Morales-Linera formula garnered 64 percent of the vote. This is how the management season began.

This is the second key to understanding the Bolivian bonanza: a new political order that enabled the administration of nationalized resources at a high-priced stage worldwide of the commodities that the country exports.

This is described by the sociologist Fernando Mayorga: “It is a scheme of government based on a presidentialism reinforced by the existence of a hegemonic capacity of the MAS: three electoral victories with an absolute majority, and the last two efforts with the control of the two legislative chambers with a qualified majority (two-thirds). This translates into unprecedented political stability.”

Bolivian model

Evo Morales always had a powerful anti-capitalist and anti-American rhetoric. His party is called “Movement to Socialism” and his vice president once wrote about a model he called “Amazonan Andean Socialism”. Is Bolivia an exponent of 21st-century socialism?

“Bolivia has its own model and does not copy anyone. I also do not know in detail the model of socialism of the 21st century, but it is clear that we differ from the rest of the processes because ours is a model of our own, with a particularity: ours is successful, both economically and socially. It’s a very own model, very Bolivian,” says Arce.

Certainly, the Bolivian model can boast macroeconomic stability and sustained growth over time. “Unlike other countries like Venezuela, Bolivia has been more cautious. The miracle in any case was prudence,” says economist Juan Antonio Morales, who was the president of the Central Bank from 1995 to mid-2006.

Another piece of information to consider is the fine print of that nationalization of hydrocarbons. Because in rigour there was no expropriation, but greater participation of the State in income and decisions. You could say in fact that this was almost a tax reform.

But symbology was always key in the Bolivian process. Mayorga says Morales’ political style combines radical rhetoric with moderate decisions. Morales agrees: “The government of Evo Morales is much more pragmatic than ideological. In his actions he did not go as far as his words.”

The government amassed reserves for use at the time when prices fell, as happened from 2014. Therein lies the prudence that Morales spoke of.

The risks

Evo Morales is already the longest-serving president in Bolivia’s history. But, according to Mayorga, the main danger to the economy comes hand in hand with politics. It happens that on October 20 Morales will seek his fourth election, with a new candidacy laden with controversy for several reasons.

In early 2016, the government suffered a severe setback when 51 percent voted against it in a referendum called to reform Magna Carta and remove the re-election limit.

But then the Supreme Electoral Court ruled that a 2017 ruling prevailing with the Constitutional Court upholding the right to indefinite re-election under article 23 of the American Convention on Human Rights. Morales will then be a candidate, but some sectors seek to question the electoral process and the legitimacy that may derive from them.

Today Morales leads the polls, followed by Carlos Mesa, who was vice president of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and then president until mid-2005.

As for the economy, despite its relative strength, it remains vulnerable to external swings. Specifically, exports go to Argentina and Brazil. In both cases, it is looking to reduce dependence on La Paz.

Critics also denounce the economy’s growing dependence on commodity exports, but the government belies it: “We went from exporting raw gas to having our urea-producing plants. We move forward with steel production, we exploit electricity from various sources. And lithium, which is an area with which we are starting industrialization,” says Arce.

The truth is that from the international fall in product prices that Bolivia exports, the fiscal deficit in recent years grew and since 2015 it is around 7% of GDP. But where the opposition sees a red light, the government does not see a problem because, it says, such resources are being targeted for productive purposes.

From the executive they prefer to highlight the strengthening of the internal market through public spending and redistributive measures such as double aguinaldo or various social bonds. “At some point a tax correction will have to be made. That created vulnerabilities,” Morales suggests.

Another caveat has to do with the exchange rate. The government’s strategy at this time was to have a stable and, according to the opposition, overvalued. This leads to domestic industry losing competitiveness in the face of the increasingly abundant imports arriving to meet the demand for wages that year after year gain purchasing power.

This strength of the local currency also generated another great conquest of the management of the MAS: the Bolivianization of the economy. Today the savings are no longer in dollars in banks, but are in Bolivians. While by the end of 90, 3% of savings were in Bolivians, today that figure amounts to 94%.

Despite the bonanza, several ghosts seem to stalk on the horizon: on the one hand, the potential domestic political conflict and, on the other, dependence on the international context. The u.S.-China trade war and the unstable situation in Argentina and Brazil could be a problem that the nascent productive diversification is not yet in a position to cope with.