At 81 years old, Antonio Cabriales walks completely hunched over. Age, he explains, and having spent countless days crouching and moving through narrow corridors working in coal pits left him with that physical sequelae.

“Working in the mine is very difficult, millet. You put the lamp here tied in your pants, you put the tools on your waist, and you have to go like this all the time,” he says, as he walks crouched for a few steps. And then pray to him, cut him, so that you get a good ticket. Because in the pits, unlike the mines, you get paid by the hour. And the more hours you suck, the more you charge.”

Still, despite his battered back, the man claims he is still “whole.”

“I’m still very healthy,” he says with the serious gesture and taking a cigarette to the corner of his lips, then lifting his pants above the narrow waist.

Antonio is already desperate. Eight days have passed since his 41-year-old son, Mario Alberto Cabriales Uresti, was trapped in a coal pit in El Pinabete, in the town of Sabinas, Coahuila. The miner was itching in the depths when, suddenly, he heard that from the earth emanated a rumble that exploded and released thousands of liters of water that flooded the galleries. Five miners managed to escape and climb to the surface in time, but for more than a week Mario Alberto has been underground with nine other companions.

“At my age, I don’t care what happens to me anymore,” says Antonio, fitting his cowboy hat over the forehead from which sweat slips out. I am a lifelong miner and I know all these wells very well – he raises his hand with long, bony fingers and points to the place where the elements of the Army, Navy and Civil Protection carry out the rescue work in El Pinabete. So if they don’t, I ask them to let me go down for my son.”

Read more: Rescue in Coahuila: the first descent of divers encounters obstacles; relatives trust in “a miracle”

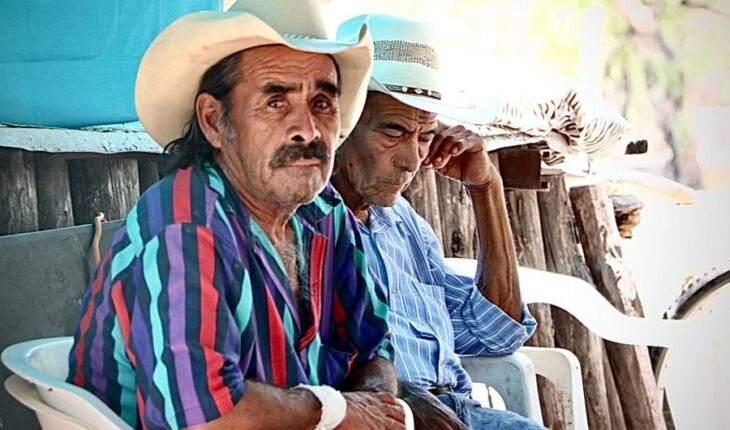

Next to the man, who takes refuge like the rest of the thirty relatives who remain waiting for news under a makeshift camp that protects them from the sun and the almost 40 degrees of the Mexican border with Texas, is Fernando Rico, another thin 55-year-old miner, with a serious face and full of cracks, leafy mustache and populated eyebrows, who wears a colorful shirt that he puts inside the jeans.

“Divers when they see that there is some wood thrown away they don’t do anything anymore. They say, ‘Oh, no, it’s that the ground in the well is very bad. There are woods. You can’t, we better leave it there,'” laments the man, who like his “relative” Antonio wears a cowboy hat worn by the years and the sun.

The men refer to the last report given by the government authorities, that on the night of Wednesday, August 10, just a week after the accident, they came out to explain that, although the rescue work had not been suspended, these will take longer than expected because, with the explosion in the mine, there is a lot of debris and turbulence in the water that prevents access and visibility in the flooded wells. Hence, Army and Navy divers emerged from the depths on Wednesday without much news.

“We are all working as a team in an exceptional way,” President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said Thursday morning at his press conference, in which it was detailed that the strategy to start the rescue consists of first extracting the water with pumps, then carrying out an exploration of the security conditions through divers and, finally, enter the rescue team in search of the miners.

However, until Thursday morning, the only achievement was reduced to the extraction of 148,000 cubic meters of water from the stricken mine, as detailed by the government of Coahuila on its Twitter account. Although for the relatives, this data does not generate any tranquility or relief. On the contrary, as the days go by, uncertainty is ripping ground, inch by inch, in the hope that a “true miracle” can still happen and the miners will come out of the wells alive.

🔴 From Sabinas, Coahuila, @ManuVPC will be reporting on the progress in the rescue work of the 10 trapped miners.

Yesterday, in a first attempt to enter, divers ran into obstacles. Read more: https://t.co/Lgnrf5OVIx pic.twitter.com/Df84UqAYtp

— Animal Político (@Pajaropolitico) August 11, 2022

Uncertainty and despair

“We are desperate. We do not get tired, nor do we deny being here, but it wears us down a lot that we do not see progress and that nobody informs us anything, “laments Cecilia Cruz Castillo, niece of the miner Sergio Gabriel Cruz Gaytan, 41 years old.

“The authorities are not being honest with the relatives. They have them here, wearing themselves out every day, and they don’t tell them almost anything about what’s going on in there,” says another woman who came to the camp with food, water and plenty of ice, as well as to provide psychological support; she is one of the many volunteers who come from the municipality of Sabinas and the surrounding communities, with a strong mining tradition, to show solidarity with the relatives in the face of the accident.

Mrs. Cecilia’s complaint is the most recurrent in the camp that presides over an image of St. Jude Thaddeus, the saint of impossible causes, along with a huge mural in fabric that a plastic artist donated.

“We ask the authorities for more information, because we are desperate. No one comes out to tell us anything. Before, they did come out to explain to us what they were doing, but not anymore. We don’t know anything,” agrees Mrs. Ana Cristina Cruz Gaytán.

Although the government of Coahuila and the federal government through President López Obrador, who usually addresses the issue in his morning conference, give general information daily about the work, the relatives denounce that much of their uncertainty is motivated by the lack of precise answers from the authorities who are working at the foot of the field. For this reason, the camp, in which there are also about twenty local, national and international media, becomes at times a hotbed of rumors that no authority confirms or denies.

Faced with the lack of certainties, Antonio desperately insists again and again that they let him down to the well. That, once more than a week has passed since the accident, you have little to lose. Anyway, he wants to reach his son, a miner also from the age of 18.

“You need someone who knows, who is a miner, to come down. That he knows the mine and knows how to move. And the soldiers don’t know how to do that. That’s why I told them to let me go down for my son. That I volunteer. But then they won’t let me and here you have me. Desperate and without news,” laments the man, who, defeated, takes a plastic chair and sits next to his relative Fernando. There, in complete silence and under a leaden heat, the two remain with their eyes set in the distance in the well where, about 60 meters deep, Mario Alberto Cabriales Uresti and nine other miners are waiting to be rescued.

What we do at Animal Político requires professional journalists, teamwork, dialogue with readers and something very important: independence. You can help us keep going. Be part of the team.

Subscribe to Animal Político, receive benefits and support free journalism.#YoSoyAnimal